The Nature of Ownership

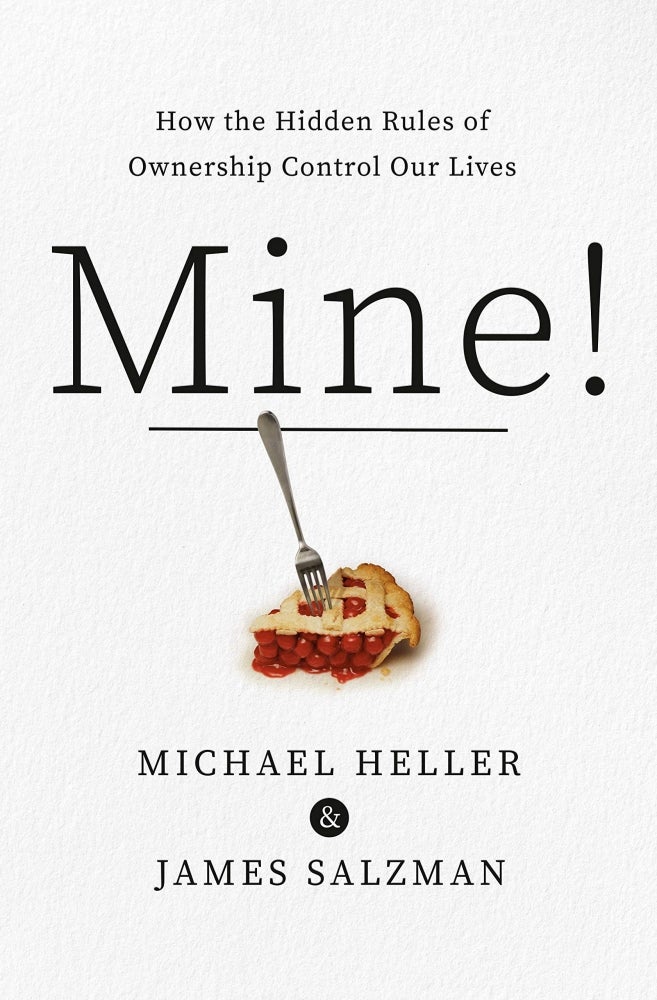

From the sandbox to the skies above, ownership is everywhere, even if you don’t see it. In their new book, “Mine! How the Hidden Rules of Ownership Control Our Lives,” James Salzman, a professor at the Bren School of Environmental Science & Management, and co-author Michael Heller of Columbia Law School take an in-depth look at how we define ownership — and how it’s defined for us — and the various ways people lay claim to things.

In a conversation with The Current, Salzman shared some insights into the ways conflicts around ownership impact our lives and how we can navigate them.

TC: Why a book about ownership?

JS: People often think of ownership rules as distant and legal and for someone else to decide. But that’s not true. We face hundreds of ownership conflicts each day without even realizing. These decide whether you are at the front of the line or the back, where you live, what medications you take, what you watch and listen to. We pass through ownership every day just like the fish that doesn’t realize it’s swimming in water.

In every culture, “mine” is one of the first words that children speak. On playgrounds, all you hear is kids shouting “mine, mine, mine!” Ownership rules the sandbox. We assume ownership is natural, obvious, simple. But that’s just not true. Ownership is always up for grabs. Once you start looking for the hidden rules of ownership, you will see them everywhere. They determine fights over reclining airline seats and whether you can share HBO passwords. Also they are implicated in big issues like climate change and wealth inequality. In fact, it’s hard to find any conflict that isn’t framed by contested ownership.

TC: You write that what’s “mine” reflects a choice among competing stories — what does that mean?

JS: It turns out that humans have just six simple stories everyone uses to claim everything in the world. Each story feels natural and self-evident. If you stop and think for a moment, though, it’s apparent that these stories are often in conflict. In fact, ownership conflicts are all around us all the time, and always up for grabs — and if you’re not the one choosing, then someone else is choosing for you.

Let’s go back to the playground sandbox. A kid sets aside his shovel and another kid grabs it. The first kid says, “This shovel is mine. I had it first!” The other says, “No, I’m holding onto it!” Their fight looks like “mine” versus “mine,” but it’s really a deeper battle between two competing stories: “first come, first served” versus “possession is nine-tenths of the law.” These are two of just six basic stories that people everywhere use to claim everything. The same stories that kids use in the sandbox also operate on the global stage. Think about who gets priority for the COVID-19 vaccines. The stakes are higher, but the battle is over competing ownership claims for who should get to the front of the line.

TC: How do businesses keep the rules of ownership hidden?

JS: Airlines are masters in deliberately creating ambiguity in ownership. Think about the last time you flew. Did you lean back? Or did someone lean their seat into your knees or scrunch your laptop? You may not think of this as an ownership conflict but, in fact, it’s a battle over control of the reclining wedge of space behind the seat. Some passengers claim the space in front of their seat for their knees and laptop. No trespassing. Others claim the space because the recline button is attached to their seat and so is the reclining wedge behind it. Here, mine versus mine is really the stories of possession versus attachment. Airlines are selling the same space twice, once for the passenger who wants to use their tray table and again for the one who wants to recline. Passengers get mad at each other, but they should be mad at the airlines for pushing the ownership conflict onto passengers to work out themselves.

TC: You’re an environmental law professor at the Bren School. Is ownership important in conserving natural resources?

JS: Absolutely. Take the example of the hit television show “Deadliest Catch.” This featured fishermen racing out in the most dangerous weather to catch crabs in the Bering Sea. This Mad Max kind of competition on the high seas was really dangerous. Many people died — exciting for TV audiences but not for anyone else. Thankfully, Alaska reengineered ownership. Today, even on “Deadliest Catch,” nobody actually dies anymore. The editors have to work harder now to create narratives of dangerous voyages. Alaska has rebuilt its rules around an ownership approach pioneered in Iceland, basically allotting a share of the season’s quota upfront to individual boats. This means that fishing crews can wait for more hospitable weather conditions, and for higher market prices. By replacing first-in-time with attachment, Alaska has made fishing safer and more profitable. Fisheries around the globe are adopting this new approach. We are using similar strategies to battle deforestation in the tropics and provide safe drinking water to cities.

What do you see as the major ownership issues of the 21st century?

Wealth inequality is surely important. Currently, about 1% of Americans control 40% of the nation’s wealth. It’s a remarkable statistic. As baby boomers die off, we are about to see the largest wealth transfer from one generation to another in human history — about $30 trillion. Most of this money will stay in the family, locking in this inequality for another generation. This concentration of wealth didn’t happen by accident but through hidden changes in the rules of ownership just in the past few decades. Remarkably, South Dakota has led the way, designing ownership rules that make it a tax haven for the super-wealthy to hide their money. As a result, everyday Americans pay more in taxes and get fewer government services. We don’t have to allow states like South Dakota to impoverish the rest of us. But to fix the problem, first, you have to know how ownership really works. That’s why we just published an Opinion piece in the Washington Post on this issue.

TC: Do the internet and sharing economy mean the end of ownership?

JS: Not at all, but we have to think about ownership differently as we switch more and more from possessing things to accessing ones and zeroes. Physical possession taps directly into our animal territoriality. These instincts run so deep that they actually predate humanity. When you hear kids on a playground saying “That’s mine!” they are invariably fighting over some tangible thing like a toy — never over a joke or story. The sense of possession hardwired into our brains has a strongly physical aspect.

Less tangible property (intellectual property, copyright, patents, all this stuff at the center of our online lives today) just doesn’t really feel much like property to most people. But businesses are working to reengineer possession to activate our physical intuitions for this intangible world. That’s why DVDs open with those scary Interpol notices that “Piracy is not a victimless crime.” We are shifting from ownership of something – some thing – to a stream of one’s and zero’s, and we didn’t evolve to think like that.

The sharing economy is different. With the internet, we think we own more than we really do. With the sharing economy, we intentionally don’t want to buy anything. As a result, some people are breathlessly claiming: “This is the end of ownership! Don’t buy car; just hail an Uber or Lyft.” But ownership is not disappearing in the sharing economy — just the opposite. Ownership is being concentrated in a smaller handful of increasingly powerful companies, controlling ultimate access to more of the basic services in your life.

You might own your iPhone, but if you fail to keep up with payments to your service provider, they can take away access to the information on this phone. It ends up being a useless paperweight. They can shut you out from your entire life. That’s a whole different kind of concentrated ownership.

TC: Your book has been featured in the New Yorker, New York Times Sunday Book Review, Forbes and other major outlets. Why do you think there has been such interest?

JS: We all think about ownership all the time, we just don’t realize it. This book shines a light on what has always been around us. The rules of ownership turn out to be really interesting, and really important. Ownership is always up for grabs. There is no natural, right answer for who gets what. At its core, the battle over scarce resources is a storytelling battle. Businesses and governments choose the story that quietly and powerfully steers you to do what they want. But ownership is always a choice. If you’re not the one choosing, then someone is choosing for you. Once you know how ownership really works, you can’t un-see it. And once you can see it, you can start to change the story as a consumer and a citizen.