‘Intelligence Plus Character’

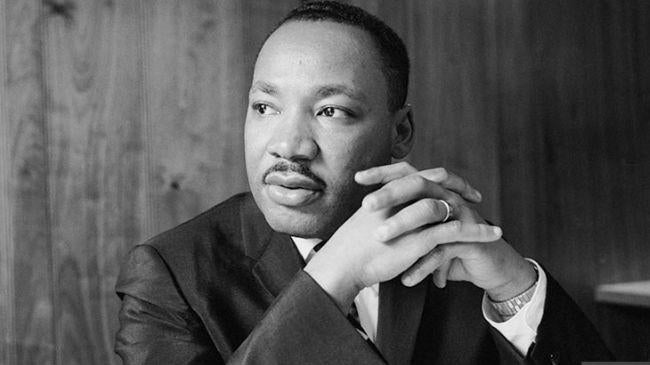

When Martin Luther King Jr. stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in August 1963 and uttered the words “I have a dream,” he spoke to a nation mired in bitter struggles over civil rights and social and economic injustice.

As we celebrate what would have been King’s 92nd birthday, scholars at UC Santa Barbara reflect on the civil rights leader and his work, his continuing relevance and how he might have responded to recent events at the Capitol Building that prove those bitter struggles are far from over.

Gerardo Aldana, Dean of the College of Creative Studies

On this Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. weekend, I am led to meditate on two things. For one, I reflect on Dr. King’s legacy and inspiration visible in the work of my colleagues — in particular those in Black studies, Chicana/o studies, Asian American studies, feminist studies and indigenous studies, but also scattered across departments and across campus here at UC Santa Barbara. They work daily toward many of the social justice goals of diversity, equity and inclusivity that Dr. King himself hoped for. Second, I reflect on Dr. King’s work, which draws moral inspiration from his religion, but appeals to reasoned argument for his social justice goals. Dr. King wrote: “We must remember that intelligence is not enough. Intelligence plus character — that is the goal of true education. The complete education gives one not only power of concentration, but worthy objectives upon which to concentrate.” And: “The most dangerous criminal may be the man gifted with reason, but with no morals.” Without question, his own moral grounding was within Christianity, but it strikes me that his approach left room for various ethical foundations. Recognizing now that our ethics may come from different sources, but still substantively overlap, and recognizing that such overlap may provide the foundation of our collective action — that seems to be worth contemplating this weekend and in the year ahead as we face the great challenges at our doorstep.

Ingrid Banks, Professor of Black Studies

“As a non-violent activist, Dr. King would have obviously denounced the violence at the U.S. Capitol. He certainly would not have been shocked given what he had experienced and witnessed in the South and the North over the course of his lifetime. However, I believe he would have contextualized the insurrection by noting how those in power in the United States have enabled white supremacy, not unlike his critique of clergy (Christian and Jewish) who marked his activism as the problem and not Jim Crow segregation when he went to Birmingham in 1963. Still, Dr. King opined: ‘The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.’ It is my hope Dr. King’s framing of that “bend” is towards an equitable justice in both word and application as we usher in this new century and beyond.”

Jean Beaman, Professor of Sociology

Martin Luther King, Jr. and his work remain relevant today for many reasons, not least of which, is the persistence of white supremacy, as we witnessed in the recent insurrection at our nation’s capital. His legacy should inspire us to consider the multivariate ways racism is maintained, and how white supremacy can be challenged and dismantled. It is also crucial to remember King as he really was. We often remember or learn about the ’safe’ version of him, not the revolutionary he really was. For example, he was clear about the dangers of capitalism, so we need to also consider how we dehumanize and oppress others, especially the poor and working-class.

Eileen Boris, Hull Professor and Distinguished Professor of Feminist Studies

The siege of the Capitol on January 6 was not an aberration but rather a manifestation of the white supremacy that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his life struggling to dismantle. The movement he has come to symbolize stood up to angry mobs of white women as well as men. White fear of “social equality,” especially when it comes to sexuality, underscores the ways that male privilege, and what we in feminist studies call heteropatriarchy, is central to a toxic mix of police brutality and economic inequality that is with us yet. In honoring Dr. King, we salute those who have put their bodies on the line in the movement for Black lives. We have so much to learn from the Black feminists who now are moving the arc of the moral universe closer to justice.

Charles Hale, SAGE Sara Miller McCune Dean of Social Sciences

One striking element of Dr. King’s brilliance was his capacity to meld two very different messages into his discourse and political practice. On the one hand, he inspired us with invocations of love, non-violence, and equality, painting a picture of the good society that we could come together to forge. On the other hand, he offered profound and unflinching diagnoses of the barriers to this emancipatory path — naming racism and other noxious inequities not as attributes of individuals but as historically embedded, deeply ingrained features of American society. We urgently need both these messages today, as we come to grips with 6 January 2021. When politicians and pundits respond to the terrorist attack on our Capitol with the disavowal, “this is not us,” they echo the first message and willfully ignore the second. They invoke U.S. exceptionalism, which only makes sense if we wish away the powerful forces that created Jim Crow, opposed the Civil Rights movement, and have worked to block or erode its achievements ever since. The logic of Dr. King’s second message — well illustrated, for example, in his 24 March 1965 address in Montgomery — leads us directly to analysis that connects the January 6 attacks with a broad swath of US society that either actively affirms white supremacy, or views racial inequality as acceptable collateral damage in the pursuit of particular interests. These millions of people, and the politicians who represent them, are a constitutive part of what and who America is. One hopeful silver lining of this horrific episode is to have buried US exceptionalism — at home and across the globe — thereby opening new space for a forthright and rigorous affirmation of Dr. King’s dual message to guide us forward.

Nelson Lichtenstein, Distinguished Profesor of History

In 1952, when Martin Luther King was a 23-year old grad student at Boston University School of Theology, he wrote a love letter to Coretta Scott. Along with the warm, affectionate phrases came a harder-edged sentiment: “I am much more socialistic in my economic theory than capitalistic,” he told his then girl-friend, “capitalism has outlived its usefulness.”

King rarely advertised such views, or used words like capitalism and socialism, after his persona became interwoven with the fate of the great social movement into whose leadership he had been thrust. King was first and foremost a preacher, a Christian, and the tribune of a multiracial, multi-stranded struggle to eradicate the most overt and obnoxious forms of discrimination and disempowerment. And in the 1950s and early 1960s, he knew that his enemies were on the lookout for any unorthodoxy they could use to slander that movement with the vilest sort of red-baiting.

When it came to economics, King was not a systematic thinker, but he had the fundamentals down right. Whatever the rhetoric he deployed, he held that the liberation of black America could not take place without a radical transformation of the economy and the politics that made it so inequitable. In 1961 he told a meeting of black unionists, “Call it democracy, or call it democratic socialism, but there must be a better distribution of wealth within this country for all God’s children.” His effort to fuse the quest for civil rights and economic justice grew stronger in the next few years. Just days before he would be assassinated, leading a Memphis strike of sanitation workers, King told The New York Times, “In a sense, you could say we are engaged in the class struggle.”

Today, when people of color constitute the vast majority of all those Americans denoted “essential workers”; and when polls show that more than half of all young people hold a positive view of “socialism,” Martin Luther King’s not-so-hidden critique of U.S. capitalism seems more cogent and motivating than ever before.

Giuliana Perrone, Professor of History

Dr. King understood that the struggle for justice and equality would be ongoing. While the events at the Capitol may seem shocking, they are an important reminder that the struggle is far from over. We would do well to consider how our mission at UCSB fits into that struggle. As King himself remarked, “The function of education is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. Intelligence plus character — that is the goal of true education.”

Victor Rios, Professor of Sociology

And as long as America postpones justice, we stand in the position of having these recurrences of violence and riots over and over again. Social justice and progress are the absolute guarantors of riot prevention. — “The Other America,” March 14, 1968.

It would seem that this quote from Dr. Martin Luther King was referring to January 6, 2021, when a large mob of predominantly white male Trump supporters terrorized the halls of democracy at the US Capitol. However, Dr. King was referring to the on-going protests and unrest that were taking place in the 1960’s. He knew these moments of crisis would never go away until a true Social Justice was implemented in all institutions and fabrics of social life in America. He understood that providing adequate resources to marginalized communities, creating education campaigns to eradicate hate and xenophobia, and holding proponents of hate and violence accountable, were the only ways to nourish U.S. democracy. Dr. King taught us that our democracy is delicate, often and consistently, showing its dark underbelly to racialized populations and allowing white privilege to flourish and claim a relentless entitlement in American life. It is time to heed Dr. King’s message and prevent future violence by implementing social justice policies and practices in government, law enforcement, education institutions, and the workplace.

Paul Spickard, Distinguished Professor of History

We Americans have long since turned Dr. King into our conveniently domesticated saint. Little children learn about him in kindergarten — that he taught Americans to love one another — at the same age they learn to share their toys and not to hit their classmates. And they learn to sing “We Shall Overcome” because it’s easy to sing (it has only eleven words and six notes). Most Americans have come to see race as a matter of being nice or not.

But race is not about niceness. Race is about power, rejection, and abuse. Dr. King was not a saint. He was a human being with flaws and frailties. And he was more than a saint. He was a man who dared to stand up for what was right, regardless of the consequences.

We live in a terrible time. Death stalks the land. Misguided fools commit terrible acts against our country and our people. We put babies in cages andseparate them from their families, just for spite. Police kill Black and Brown men and women indiscriminately. We could use some leaders like Dr. King right now: tough, articulate people who can face hard things with courage, resolve, and generosity of spirit. It’s going to take us a long time to climb out of the pit of hatred, cruelty, and suffering we have created these last few years.

Dick Startz, Professor of Economics

As we pass out of the most disruptive year in America since 1968 — the year Dr. King was gunned down — I wonder what Dr. King would have made of the violence the nation has undergone. The first answer is clear. Dr. King condemned riots. In his speech “The Other America,” Dr. King said “… I will continue to condemn riots, and continue to say to my brothers and sisters that this is not the way.”

Dr. King would have had no sympathy for the attempted putsch by the Capitol Building insurrectionists. He went on to write, “a riot is the language of the unheard.”

We know, though, that the attack on the Capitol was encouraged by those with loud, influential, and public platforms.

Dr. King understood that attacks on democracy cannot be ignored. He wrote in the same address, “And I’m absolutely convinced that the forces of ill-will in our nation, the extreme rightists in our nation, have often used time much more effectively than the forces of good will. And it may well be that we will have to repent in this generation not merely for the vitriolic words of the bad people and the violent actions of the bad people, but for the appalling silence and indifference of the good people who sit around and say wait on time.”