The Status of Women

What drives people seek to high social status? A common evolutionary explanation suggests men do so because, in the past, they were able to leverage their social position into producing more children and propagating their genes.

Indeed, much evidence shows that high social status grants men a number of benefits, not the least of which is increased access to sexual partners. Consider Genghis Khan, who, according to some historical estimates, fathered upwards of 1,000 children with his numerous wives and over 500 concubines.

And more recently, there’s Winston Blackmore, the leader of the polygamous Latter-Day Saints group in British Columbia, who is said to have 149 children with his 27 “spiritual wives.”

But what about women, for whom fertility is biologically constrained? Pregnancy, after all, is a nine-month endeavor, followed, in traditional societies, by another several years of breastfeeding. Realistically, over the course of her childbearing years a woman can’t expect to give birth to more than 20 or so children, and that’s assuming she devotes herself entirely to reproduction.

Given these biological limitations, how might women benefit from high status? Do women have the same motivations for status striving as men do?

New research by anthropologists at UC Santa Barbara suggests that a woman’s status does pay off, but in the form of better health outcomes for her children. Studying the Tsimane, a population indigenous to the Bolivian Amazon, the researchers found that the children of politically influential mothers are less likely to be sick, and more likely to be of healthy weight and height for their age. Their work appears in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

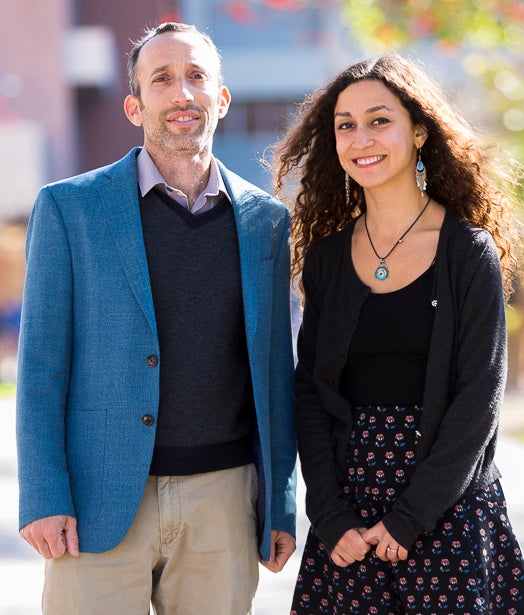

“When we think about social status, it’s often linked — for men at least — to more wealth and sexual partners and to higher fertility in places without birth control,” said Sarah Alami, a doctoral student in anthropology at UC Santa Barbara and the paper’s lead author. “But since women can never have as many children as men can, does this mean that status striving is an exclusively male privilege?”

The answer, according to the researchers, is no. “Women may just have different motivations for seeking status than men,” Alami continued. “This paper proposes that women may be more likely to leverage their status into greater resources in a way that can benefit their existing children.”

To measure status in a context of minimal material wealth, the researchers asked men and women to rank all the people in their community in terms of who has the greatest political influence, whose voice carries the most weight during community meetings, who is best at leading community projects and who garners the most respect.

When they compared those rankings against several measures of health for children, they found children of politically influential women fare better than others, those children grow faster and also are less likely to be diagnosed with common illnesses such as respiratory infections, gastrointestinal diseases and anemia. Respiratory infections are a source of morbidity and mortality in the Tsimane population.

“So much work on status focuses only on men because male status striving, leadership and power wrangling is so in-your-face,” said Michael Gurven, a professor of anthropology at UC Santa Barbara, co-director of the Tsimane Health and Life History Project and the paper’s senior author. “We wanted to measure women’s status in a relatively egalitarian society, even where most formal leaders are men, to see how variable it might be, and how it matters in daily life.”

The study goes beyond simple correlations between status and health, Gurven continued. “Maybe there’s no causal relationship — perhaps healthier people just have healthier children. Such an explanation doesn’t require extra resource access or others’ deference,” he said.

“But if it was just a matter of having good genes, we’d expect similar effects from both mother and father — since each contributes genes,” he went on. “But we don’t see that. Dad’s status has a positive effect on child health, but it’s relatively weak and disappears once we include mom’s in the same statistical model. So that suggests either the mother’s influence has a stronger effect on their children, or the father’s influence works through the mother’s.”

So, how does a woman’s political influence lead to better health outcomes for her children? The authors first tested whether greater material assets, schooling, wages and kin connections could explain the relationship. While status exerts some of its effects on child health via these mediating forms of wealth, combined they explain relatively little. A number of other tests and control variables also did not alter the relationship between women’s status and child health. Instead, the authors propose that a woman’s publicly recognized influence affects her ability to be heard within her household. And having a voice can directly benefit children.

The researchers collected data on the amount of power husbands think their wives have. This includes men’s opinion about the decision-making authority of their wives in different domains, and their attitudes toward women in general, women working and women being educated. “We found women’s political influence was correlated with their husbands having more gender-egalitarian views, their husbands thinking, for example, that it’s okay for a woman to have opinions that differ from her husband’s,” Alami said. “And women’s influence was also correlated with their husbands thinking their wives have a say in household decisions such as where to live, when to travel and how to spend household money.”

Added Alami, “The fact is that even in a context where women have nine kids and where her efforts aren’t flashy or accorded much cultural value, women can still be well respected and have high status.”

A lot of this work, Gurven commented, is inspired by evolutionary or “ultimate-level” questions. “Of course we don’t crave status because we’re consciously thinking about increasing reproductive success,” he said. “Women are not walking around saying, ‘I’m going to become influential so that I can improve my children’s health and survival.’

“But any discussion here would be lacking without considering the costs and benefits of climbing the status ladder,” he continued. “What’s the point of putting so much time and effort into something elusive like status if there’s not some benefit? We’re saying that payoffs are there for women, too, and that women may have similar status motivations as men — we just find that fitness payoffs for women are not from greater sexual access, but instead improved health and other outcomes for children.”

One of the strengths of this study comes from the researchers’ ability to measure status — a challenging thing to do. “I can measure your height or your weight, and I can ask how much money you make. But status — what others think of you — is not so straightforward to measure,” Gurven explained. “But it is really important in human social lives, affecting so many of our behaviors and motivations.”

Added Alami, “Everyone was rated by a representative group of village residents. That means all were judged by the same yardstick. And it turned out the average woman did rank lower than most men in terms of social status, but there was substantial overlap between men and women And in a previous recent study, we showed that the sex difference in political influence disappears once you account for a person’s size, formal education and number of cooperation partners — suggesting that these factors, rather than gender per se, lead to high status.”

Coincidentally, the authors’ paper appears during Women’s History Month in the United States, shortly after International Women’s Day and in the wake of six female Democratic presidential contenders having vied for their party’s nomination. While the work cannot explain why far fewer women than men hold positions of power, it is consistent with studies showing that more female political participation is desirable for improving child welfare. For example, a critical mass of women’s political representation in low- and middle-income countries has been shown to lower infant mortality (https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.6.2.164) and increase vaccination rates (https://academic.oup.com/sf/article/91/2/531/2235851).

The current study suggests that even in isolated, rural traditional populations, and without holding formal leadership positions, women have motivations for taking on those positions. But they face different constraints.

“There are these trade-offs and divisions of labor that are influenced by cultural context,” said Alami. “If women were able with more flexibility to have children and yet maintain the same social networks and obtain the same educational and work opportunities, you would see less of a difference in perceived status between men and women.”

Co-authors of the study include Thomas Kraft, a postdoctoral scholar at UC Santa Barbara; Christopher von Rueden, a former graduate student at UC Santa Barbara and now an associate professor at the University of Richmond; Jonathan Stieglitz of the Institute for Advanced Study in Toulouse; Edmond Seabright of the University of New Mexico; Aaron Blackwell of Washington State University; and Hillard Kaplan of Chapman University.