Equal Rights or Special Rights?

The rise of the “gig economy” has engendered much fear in recent years, as more and more workers are pushed out of full-time jobs into occupations offering no guarantees and few if any benefits. While this is widely portrayed as something new and ominous, Eileen Boris would like to remind us of a group that has been working under such conditions for a very long time:

Millions and millions of the world’s women.

“Historically, most women were not in jobs that came under labor standards, such as minimum wages or occupational safety,” said the UC Santa Barbara Distinguished Professor of Feminist Studies and holder of the Hull Chair. “They were not unionized. If there were labor laws on the books, they didn’t apply to them. They could be fired at will. They were often defined as independent contractors.”

Previously, Boris studied one large group of workers who fall into that category: Home-based piece-work laborers, mostly women and often mothers, who earned a set amount for each piece of clothing they created. She also co-authored a history of home health care workers. Today, her focus has expanded from the United States to the world.

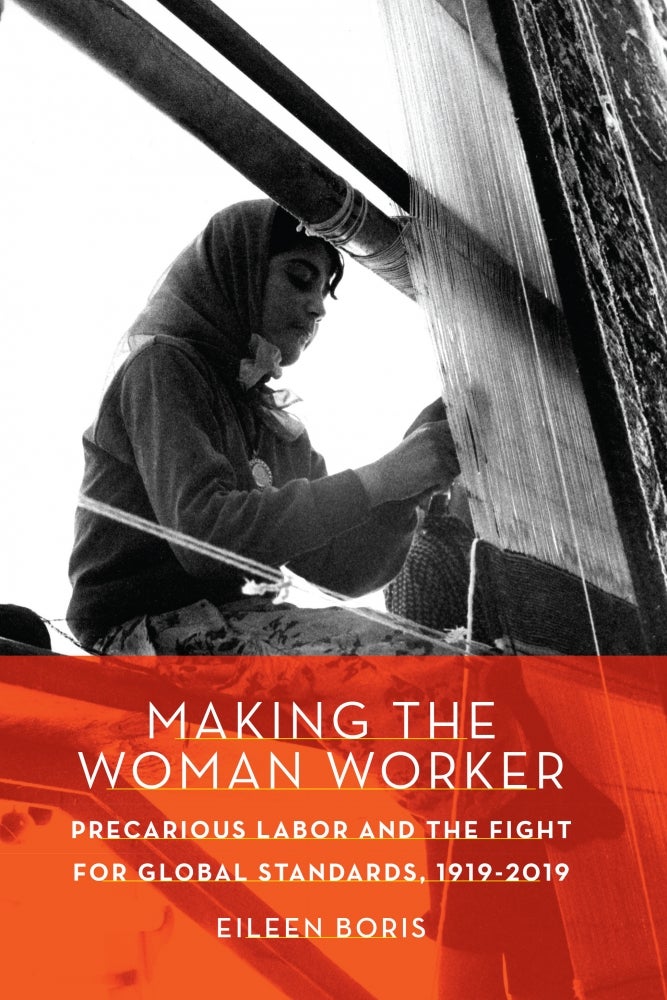

In her new book, “Making the Woman Worker: Precarious Labor and the Fight for Global Standards, 1919-2019” (Oxford University Press), Boris presents an intersectional history of labor standards. The evolution of these standards, and the discussions surrounding them, reflect changing economic conditions and persistent gender constructions — as well as still-unresolved inequalities between men and women, and among women by race, class, and nation.

She opens her first chapter with a statement British trade unionist Mary Macarthur made at the first International Labour Conference in 1919. “When the man comes home at night, his day’s work is done,” she declared. But due to her duties as mother and homemaker, when a woman worker “leaves the factory, she usually goes home to begin a new day’s work.”

Sound familiar?

“I like to tell people I have only two topics — home and work — and they’re really the same,” Boris said. To rectify gender inequality, she added, “It’s very important to expand the definition of work.”

“I argue in the book that labor standards for women workers are really about the allocation of women’s labor power, whether it’s at the home or workplace. If you don’t have social support for housework and care work, it’s very hard for those who undertake such labor to be employed in the most productive and efficient way.”

Boris’ book is based on the periodic debates and evolving guidelines of the International Labor Organization, which is celebrating its centenary this year. Along with the League of Nations, it was established by the Treaty of Versailles at the end of World War I.

“The ILO is an arena for the struggle between workers, governments, and employers,” she said. “Because women were often not in unions, labor standards were seen as an alternative to collective bargaining for them.”

Boris chronicles the push for different standards for men and women workers, and between Western industrial workers and those under colonial rule, in the ILO’s early decades. This includes the fight for paid maternity leave, an issue that came up in the organization’s first in 1919.

“One of the major themes within women’s and gender history has been what constitutes equality, and for whom,” she said. “Does different treatment lead to inequality, or can it be a road to equality? If people are not similarly situated, treating them the same may lead to greater inequality.

“On the other hand,” she continued, “targeting one group for particular measures that may cost an employer more may undermine their employment. If those classified as women must have rest breaks, or couldn’t work as long as necessary,” managers may be reluctant to hire them in the first place. The solution, she added, is to place all workers under labor standards — but that has been an incomplete process, married by inequalities within and between nations.

In her book, Boris demonstrates how complicated this debate is. “Labor standards, by definition, offer protection for workers,” she said. “But some measures are really about policing and controlling those defined as women, or as colonial subjects, through regulating the workplace.

“Night work is the best example of that. The thinking was to protect women from having to walk on the streets at night. That may have been true in some places. But it also kept women from certain jobs. Some male trade unionists wanted these protective laws to restrict women’s employment, out of the belief that the man should have a job and support a wife and children.” (These discussions focused on Western women; early standards allowed nations to exclude women in non-industrial occupations, especially in the Global South.)

The problem of a dual work day remains familiar to many — especially working-class women and immigrant women, many of whom may work as a housekeeper or nanny for another woman. Boris considers it highly significant that the International Conference of Labour Statisticians officially recognized housekeeping and caring as “work” in 2015, recommending official statistics include “own-use production.”

“It has asked governments to correct statistics and document such as a form of work,” she said. Such a shift in mindset, should it catch on, could hugely impact how we view the concept of work and the rights of workers—especially women.

Boris will discuss her book in a talk entitled “How Did an Americanist End Up Writing Transnational History?” at 2 p.m. Oct. 18 in Room 4020 of the Humanities and Social Science Building. Books will be available for purchase and signing.