Reaching Critical Mass

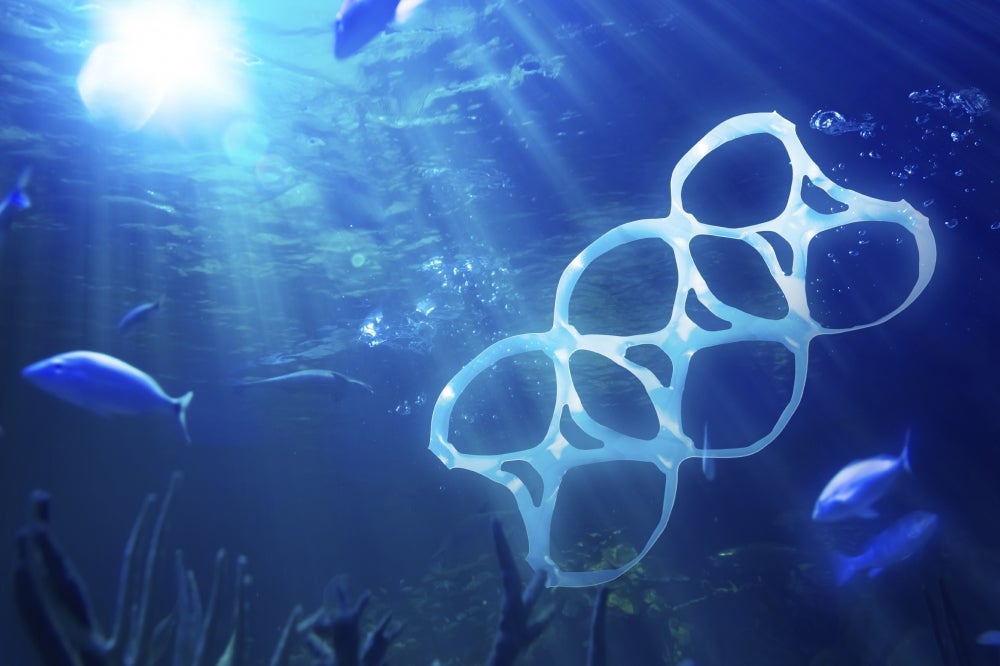

Perhaps it was the image of the dead seabird that had unwittingly ingested shards of plastic. Or the footage of the turtle precariously tangled in plastic netting. Whatever the catalyst, plastic pollution has rapidly evolved from a largely abstract problem to a clearly relatable horror. And with that, public opinion has shifted from apathetic to appalled, inspiring numerous calls to action.

“I have not met a single person who is not upset about plastic in the ocean,” said physicist and engineer Roland Geyer, a professor of industrial ecology at the Bren School of Environmental Science & Management. “It seems to be a non-controversial image. It generates a visceral response that climate change does not.”

Geyer will discuss the problem of plastic pollution, as well as the changing nature of the public’s response, on Thursday, Oct. 10, when he gives the inaugural lecture of “Critical Mass,” the Interdisciplinary Humanities Center’s (IHC) 2019-20 public events series.

“Our theme this year is taking large societal problems — immigration, incarceration, access to health care — and focusing on how individuals actually experience them,” said IHC director Susan Derwin. “The humanities can bring a crisis home on a human scale.”

Geyer, a scientist who has grown increasingly aware of the importance of the humanities, has, in a sense, been preparing for this lecture his entire life. “I can trace my interest in environmental issues to my 7-year-old self,” he said. “I remember looking at the garbage man picking up stuff from the bins and thinking, ‘Where does it go?’”

In the case of plastics, the ultimate answer often is: into the ocean. According to Geyer, much of our recycled plastic waste is shipped to less-developed Asian nations, many of which have poor solid-waste management systems. As a result, a considerable amount of plastic we smugly deposit in recycling bins might end up in the sea.

“Plastic in the ocean is the most upsetting, most visible manifestation of overconsumption of something we know how to make, but don’t know how to manage. We love new, shiny things, but we expect the old, wrinkly things to just disappear when we’re done with them.”

While we are beginning to grasp the absurdity of that belief, “It’s too early to declare victory,” Geyer added. “There’s a good chance media attention will move on, as will public interest. People might say, ‘We’ve banned plastic straws, so we’re done now.’ The issue, which I will discuss in the second half of my lecture, is how facts translate into attitudes, and how those attitudes translate into action.”

Other events in the series will explore how that dynamic plays out in other realms, from mid-20th-century urban planning to the ways in which military veterans who have found paths of healing for themselves seek to transform the way that our society understands the roots and impact of the wars we wage. Upcoming speakers include best-selling and Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jared Diamond (“Guns, Germs and Steel”), who will give a talk the evening of Jan. 15 in Corwin Pavilion.

The fall lineup of “Critical Mass” also will include Reuben Jonathan Miller of the University of Chicago. On Nov. 14, he will discuss his research on the post-prison lives of men and women who have served their sentences and are transitioning back into society. Derwin hopes he can take another large-scale issue — mass incarceration — and bring it home by telling the stories of formerly incarcerated individuals, their spouses and their families.

Miller will be followed on Nov. 21 by political activist and author Ady Barkan, who has been diagnosed with terminal ALS, otherwise known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease. “He’s using his personal situation to talk about health care and the actual impact of political decisions on individuals,” Derwin said. “He lends his voice to larger, collective issues. It seems to me this is life-sustaining activism for him. His own mortality is aligning with urgent life-and-death matters that affect all of society.”

To Derwin, Barkan’s writing is another example of how the humanities can bring a large-scale crisis into clearer focus by showing how it plays out in the everyday life of one person.

“When Ady speaks, people connect with his vulnerability and strength,” she said. “Individual voices — voices of survivors, voices of prisoners — add dimensions to issues that are otherwise on a scale that is overwhelming and seemingly impervious to change.”

Aside from Jared Diamond, all talks will begin at 4 p.m in the McCune Conference Room, 6020 Humanities and Social Sciences Building.