Digging the Scene

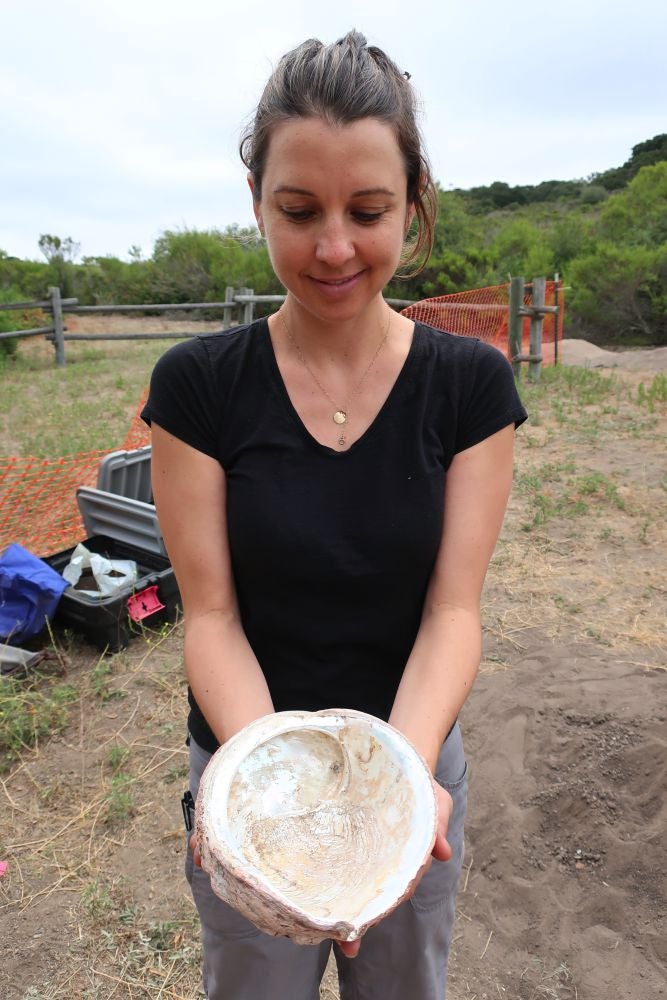

Kaitlin Brown’s prized discovery doesn’t look like much if you’ve spent time near the ocean. It’s an abalone shell — bigger than what you’re used to, but otherwise unremarkable.

And yet that iridescent remnant of a giant sea snail — Haliotis rufescens, or red abalone — is much more. Brown and her crew of anthropology students found it 1.2 meters below ground as they were excavating the site of Chumash “family apartments” at La Purisima Mission State Historic Park in Lompoc.

“It was a very charged moment,” said Jenny Altamirano, a UC Santa Barbara anthropology student who is participating in the dig.

Brown, a UC Santa Barbara doctoral student in anthropology who is leading the excavation, said the abalone was unique in that other shell fragments they’d found were mussel. The abalone first appeared as a small piece sticking out of a sidewall. Careful work eventually brought the artifact into the light for the first time in more than 200 years.

“It was a charged event because we had no idea how big it was and slowly, as we started getting deeper and deeper into the sidewall, we realized how massive it was,” Brown explained. “After we excavated the whole abalone out, I handed it over to the Native monitor, passing the abalone that appeared to be deliberately placed by a Mission resident a few hundred years ago into the hands of a Chumash tribal descendant.”

Field School

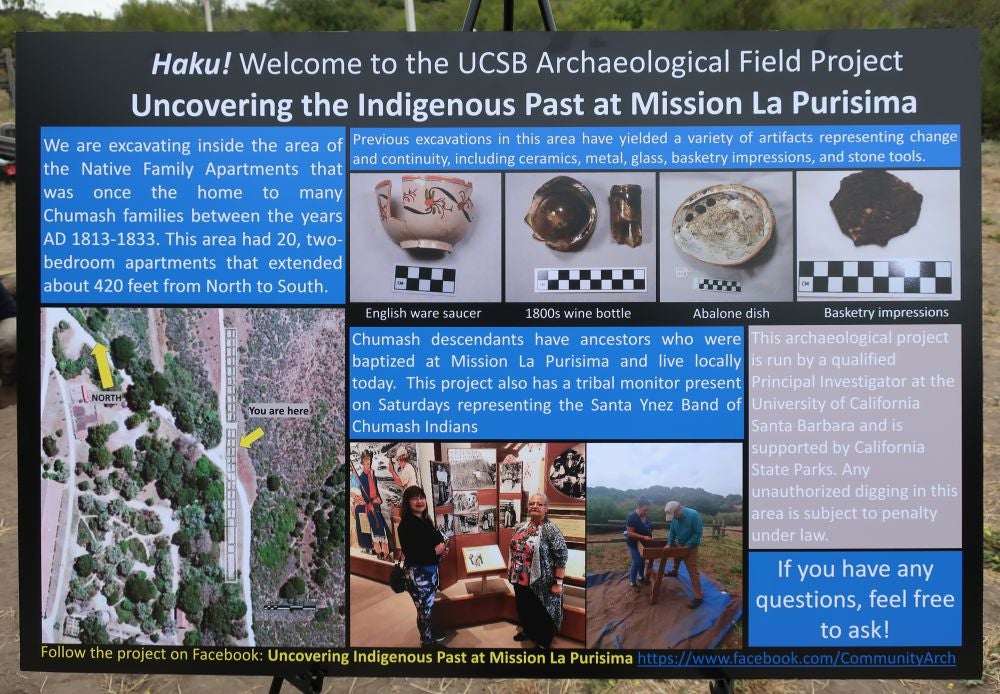

The work at the mission is part archaeology project, part classroom for Anthropology 181, “Methods and Techniques of Field Archaeology,” which Brown is teaching. Conducted over six Saturdays, the field class wrapped up Aug. 3, though Brown will continue to visit the site in the fall. She spent two years preparing for the dig, poring over records of previous excavations in the 1930s, ’50s and ’60s.

She identified a 7-meter window of ground where she suspected she would find rooms in the apartment that hadn’t been excavated. “We plopped right down on one,” said Brown, who specializes in archaeology. “And we found a floor.”

Additional excavation revealed roof tiles that had collapsed and two strata of floors, where they found glass beads (introduced by Europeans), soapstone vessels — and the red abalone shell.

“The stuff being found behind the apartments is really interesting, too,” Brown said, “because there are a lot of shell beads and shell bead-making detritus, so the Chumash, even in 1813, are still making beads here.”

A Focus on Sensitivity

The Chumash family apartments are split into two eras: the Spanish period, 1813-21, and the Mexican period, 1821-33. Brown’s work focuses partly on “sustained colonialism” — how Native Americans negotiated multiple waves of foreign rule over long periods of time.

“I’m interested in how the Chumash who lived here navigated these two different colonial policies,” she said.

For contemporary Chumash, excavating the land of their ancestors is a sensitive issue, and it’s one of the reasons a tribal member monitors the work in progress. Gina Mosqueda-Lucas of the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians keeps a close eye on the project “to make sure the artifacts are coming out of the ground respectfully.” She likes what she’s seen.

“Katie really has a great group of students here, who are very respectful of the culture,” Mosqueda-Lucas said. “They’re always asking questions about language, about these items that are coming out of the ground, the things that they’re finding. They ask for the purposes within the culture — what they’re used for. So they’re really good at asking questions, and not just pulling artifacts out of the ground.”

That attention to cultural sensitivity is intentional. Brown said the practice of archaeology has evolved from the simple extraction of artifacts to embracing cultural context and collaborating with indigenous people at the heart of the work.

“I think the main thing I’m trying to teach is, with the presence of the monitor, how important it is these days to really work with the local community,” she said. “Other Chumash tribal descendants and Chumash youth have come out to the mission. I’ve put them in a unit, getting them involved. That’s a part of it: to show how archaeology has changed. It’s not just about digging up the past; it’s really about what we’re calling attention to in the present.”

A Learning Experience

Brown has 12 students and two volunteers working the dig, most of whom are the older, non-traditional variety. Angelina Sanchez, 34, will be a third-year UC Santa Barbara anthropology major in the fall. An excavation, she said, gives potential archaeology students a real sense of what work in the field entails.

“Do something like this first because on one hand you’re like, ‘Wow, I really love doing this.’ And on the other hand, you may be like, ‘You know, it’s hot out, you’re covered in dirt, it’s tiring.’ Some people may find it boring,” Sanchez said. “But you get to really see if it’s what you want to pursue. You have to have a level of passion and interest and commitment to find this gratifying.”

Ely Rareshide spent 10 years as an engineer before deciding “people are more interesting than windmills” and becoming a UC Santa Barbara sociocultural anthropology doctoral candidate. “It’s really nice not to be staring at my computer screen,” she said. A veteran of other field school digs, she likes that the work requires her to practice a kind of dusty mindfulness.

“It’s very meditative, because it’s so physical you have to be focused in the moment as you’re digging and when you’re screening,” Rareshide said. “You get this nice mental break, which I really like. You’re out, seeing new things. You’re seeing stuff that people haven’t seen in hundreds, perhaps more, years, depending on what type of site you’re digging.”

With the dig complete, Brown and her students will analyze the vast amount of data collected. They’ll present their findings at the Society for California Archaeology’s annual data-sharing meeting at UCSB’s Sedgwick Reserve in the Santa Ynez Valley in October. She also hopes to put together a symposium at the society’s annual meeting in 2020 where her students will present their research.

“What we’re doing is, we’re going to be comparing what’s happening in the mission versus outside the mission,” Brown said. “We’re using a bunch of data that’s already been collected at historic Chumash villages in the Santa Ynez Valley and comparing it to what we are finding here.”