Sacred Spaces

As religious studies scholar William Elison tells it, the crowded streets of Mumbai are filled with homemade holy spaces, erected covertly and without any sort of official permission from government or landowners.

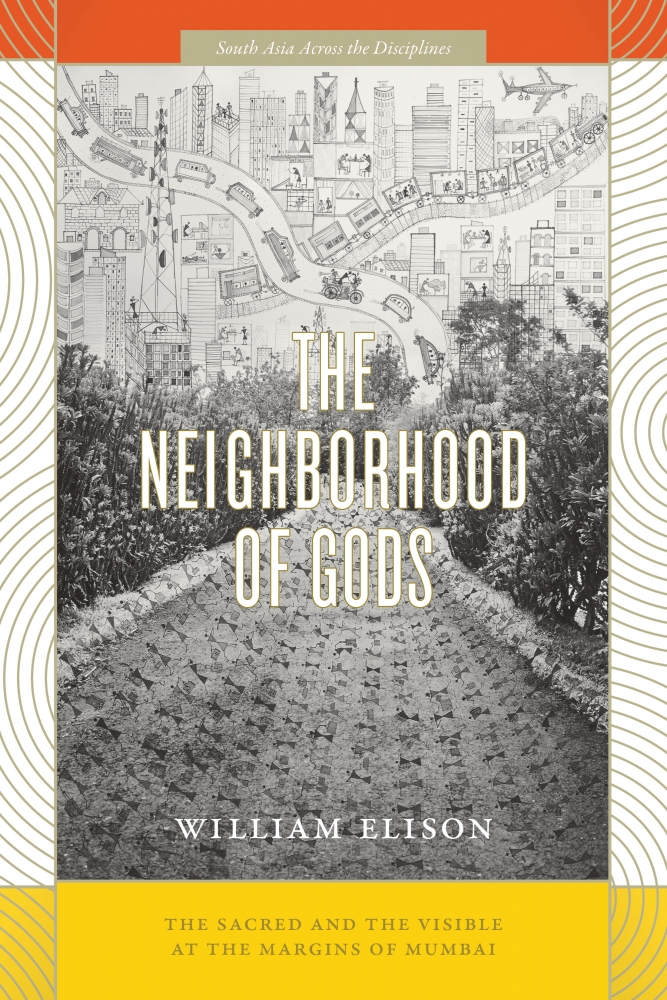

These shrines and temples are now the subject of a new book by the UC Santa Barbara professor, who specializes in South Asian religions and visual culture. In “The Neighborhood of Gods” (The University of Chicago Press, 2018), Elison examines the phenomenon of urban gods and their illicit sanctuaries.

In the book, Elison argues that, while easy for outsiders to romanticize, these structures exemplify issues of ownership, divinity and authority in modern India. “If you study religion in India or South Asia, you are familiar with the idea that peasants worship divine figures that are placed locally on the landscape,” he said. “For example, if you live in a village at the foot of a mountain, there’s a god who lives on the mountain.”

But, Elison explores in his writing, how does the same practice translate to a bustling city?

Examining how marginalized communities try to legitimize their deities in the eyes of others, the book focuses on Mumbai in part because it is India’s showcase city, the glamorous home of the Bollywood film industry. “I’m trying to get beyond the strangeness of gods in the city,” Elison explained. “I’ve chosen to work in Mumbai, which I think in the minds of many Indian people is an especially incongruous place to look for local gods, because it has an image as being the most modern, glossy metropolis in India. Nevertheless, for lots of people who live there, there’s a saint at the street corner and a powerful presence inside the little temple on the sidewalk.”

The practice of building shrines or temples on public land can create some conflict, which Elison also details in his book. “By definition, the city street is traversed by members of the public,” he said. “If you’re a local person and you’ve put up a shrine on the sidewalk, you run into trouble not just from the city government whose property you are encroaching on, but also from everyone walking on the street who doesn’t recognize the same gods you do.”

There is even sometimes conflict with people who do practice the same religion. Elison describes Mumbai as densely populated, with between 12 and 13 million people living within an area three-fifths the size of New York City. “The majority of people would identify as Hindu, but it’s a very diverse religious identity,” he explained. “So, while some Hindus are building temples on the street, other Hindus object to that practice.”

Drawing parallels between building housing on public land and building temples on public land, Elison proposes that the practice breaks down along class lines. “You can connect the people who tend to build clandestine or unauthorized temples on land that technically belongs to the government or someone else with people who build their houses on land that technically belongs to someone else,” he said. “Over half of the population of Mumbai live in slums. I view this as two sides of the same phenomenon. People build houses for themselves that are unauthorized and those same people build houses for their gods or saints that are unauthorized.”

“The Neighborhood of Gods” also delves into issues of religious authority and representation at the major Bollywood film studio Filmistan. Located in a suburb of Mumbai on land considered sacred by an indigenous ethnic group, the studio is an interesting example of a space that contains both local gods and a number of structures meant to resemble religious spaces. “There’s a Hindu temple in the middle of the studio and it’s a permanent set,” Elison explained. “It looks more like a Hindu temple than a real temple, because it’s shiny and professionally designed. Some people say that it was built on top of a real temple that belonged to an indigenous tribal community. If you ask what happened to the god who resided in that temple, you get very different answers depending on who you’re talking to.”

To answer complex questions about religious ownership, the book draws on conventions of ethnography and traditional narrative storytelling. Elison interviewed a number of people involved in the creation or maintenance of shrines to local gods in Mumbai, and formed lasting relationships with some of his subjects. His decision to include their voices and words in the book echoes issues of representation and legitimization that he explores in his work.

“The picture of Mumbai that you get from a modern Bollywood film is a very select and sanitized picture of a gleaming metropolis full of happy, prosperous people,” Elison said. “I’m not saying that’s not at all true, but it’s just the most visible tip of the iceberg. The rest is full of stories that aren’t told. Part of what I’m trying to do in the book is to represent the ideas, experiences and modes of living in the city of the people who tend not to be represented.”