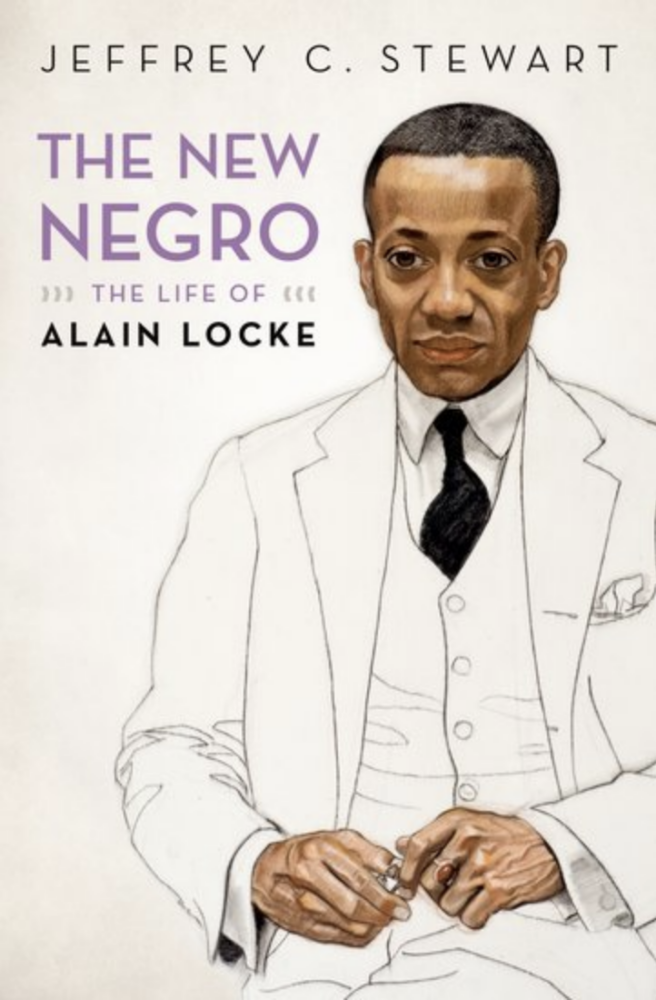

Pulitzer Prize Winner

Scholar Jeffrey C. Stewart has won the 2019 Pulitzer Prize for biography for “The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke,” his meticulous and sensitive biography of the African American philosopher and activist who was a central figure in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s.

The award was announced Monday, April 15.

“I send my wholehearted congratulations on behalf of our entire proud Santa Barbara campus to Professor Jeffrey Stewart on receiving the 2019 Pulitzer Prize in Biography for his book ‘The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke,’ which illuminates the life of an important historical figure,” said Chancellor Henry T. Yang. “This most prestigious honor is a testament to Jeffrey’s brilliance and perseverance as an exemplary researcher, teacher, scholar and writer. We are immensely proud of and absolutely thrilled about his tremendous achievement. That the announcement of the award comes during the 50th anniversary of our Department of Black Studies is both inspirational and serendipitous.”

The honor follows Stewart's winning the National Book Award for nonfiction in November 2018. In accepting that honor, Stewart praised Locke as a man who nurtured an artistic community while he himself suffered as a man apart.

“As a gay man who lived a closeted life, he had many struggles, and one of them was with tremendous, crushing aloneness,” Stewart says. “So when I stand here I think about his achievement, and what that was to create a family among writers and artists and dancers and dramatists, and call them The New Negro. The basis for a new creative future — and not just for black people. A new negro, for new America.”

Charles Hale, the SAGE Sara Miller McCune Dean of Social Sciences, called the award a proper validation of Stewart's talents as a scholar and writer.

A Respected Scholar

Stewart was a graduate student when he first encountered Locke. College students discover and forget historical figures every day, but something about Locke intrigued Stewart, today a professor in the Department of Black Studies.

Locke had certainly earned the respect of history. He was the first African American selected for a Rhodes Scholarship, taught philosophy at Howard University for nearly four decades and was a crucial figure in the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s.

And yet Locke is little remembered today, a seeming footnote in the long African-American struggle for equality. “He’s under-appreciated and kind of an invisible man,” Stewart said.

That could change with “The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke” (Oxford University Press, 2018), Stewart’s meticulous biography that retraces the footsteps of the philosopher/activist from his early days in a middle-class Philadelphia family to Harvard and Europe, and the tightrope he walked as a gay man.

Locke’s life was extraordinary by any measure. He mentored such luminaries as Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes. He was a cultural pluralist who believed that the path to equality for African Americans was through self-improvement and the arts. His influence as an advocate for African art and an enduring black aesthetic carried well into the 1960s.

‘The New Negro’

His landmark anthology of African American works, “The New Negro,” laid out his vision of cultural pluralism and was viewed as one of the most important works of literature of the age. Published in 1925, it established him as the “dean” of the Harlem Renaissance.

As the decades passed, however, Locke slipped into history’s shadows. Stewart argues, in part, that he was eclipsed by what he called the “dominant poles” of African American leadership in the early 20th century: Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois. Washington, born a slave, called for disenfranchised blacks to embrace education, entrepreneurship and conciliation as a way forward. Du Bois, meanwhile, denounced capitalism and racism, and a was a forceful advocate of African American equality.

Locke’s philosophy fell somewhere between the two. An intellectual with a distaste for conflict, “He really didn’t like protest as the main approach to racial interaction,” Stewart said, explaining that Locke felt it put too much emphasis on the other side. “In other words, you’re reacting to what they’re doing, trying to convince them to change, instead of building up your own resources.”

A Complicating Factor

Complicating his life was being a gay man in an era long before it was acceptable. As Stewart tells it, Locke was something of a dandy and a complicated man to start with, and being gay made it harder for him to navigate the layers of society he moved through.

“And so he didn’t really fit into this aspect of black middle-class culture,” Stewart said, “which was called respectability: you make sure that everything about your life is middle class and bourgeois and a kind of mirror of heteronormative middle-class life. And this ideology held out the hope that if you mimicked that life, you would be accepted, assimilated and integrated into society. Sexual conformity was a big part of it.”

As Stewart relates in “The New Negro,” Locke’s private life was fraught, bordering on tragic. He was a lonely man whose search for love and acceptance was marked by frustration. In a heartbreaking chapter, Stewart recounts Locke’s desperate and doomed attempts to win over a young and dashing Hughes with holidays in Paris and Italy, and promises to support him if he came to Howard.

Their story, Stewart writes, “is more one of pathos and unrequited love than naked exploitation. Locke did not want a prostitute — he wanted a companion, a partner who lived with and inspired him.”

Maternal Influence

In a way, Locke’s loneliness — and greatness — began the day his mother died. In the extraordinary opening chapter, Stewart recounts that upon her death in 1922 Locke honored his mother with an unusual wake. When guests arrived they found “the deceased Mary Locke propped up on the parlor couch, as though she might lean and pour tea at any moment. She was dressed exquisitely in her fine gray dress, her hair perfectly arranged. She even had gloves on. Locke invited his guests to ‘take tea with Mother for the last time.’ ”

As strange as the wake was, the death of Locke’s mother allowed him to break with her bourgeois tradition and formulate his own notion of “The New Negro,” who, Stewart writes, “was a cultural giant held down by White Lilliputians …” Locke believed that “all that was needed was for this giant to throw off the intellectual strings that bound this intellect to self-pitying despair about Black people’s plight in America, and assume his or her true role — as architect of a new, more vibrant future called American culture if those in his or her path would just get out of the way.”

A Survivor and a Leader

The disparate elements of Locke’s life — the intellectual vibrancy, the sadness, the resilience — made him an exemplar of a survivor, and a leader, in a difficult age, according to Stewart.

“I think that all of us have the power of self-invention and re-invention,” he said, “and part of that comes from being willing to step into our power. And this is kind of a universal philosophical position, but one he felt had particular resonance within the black experience. It’s a message as relevant today as it was during Locke’s lifetime.”