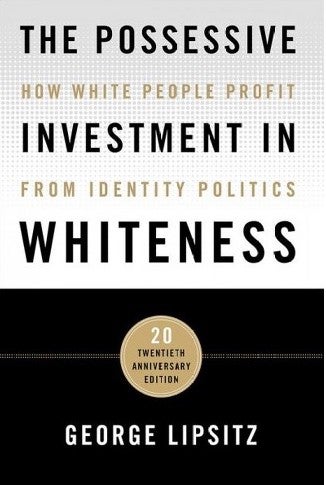

‘The Possessive Investment in Whiteness’

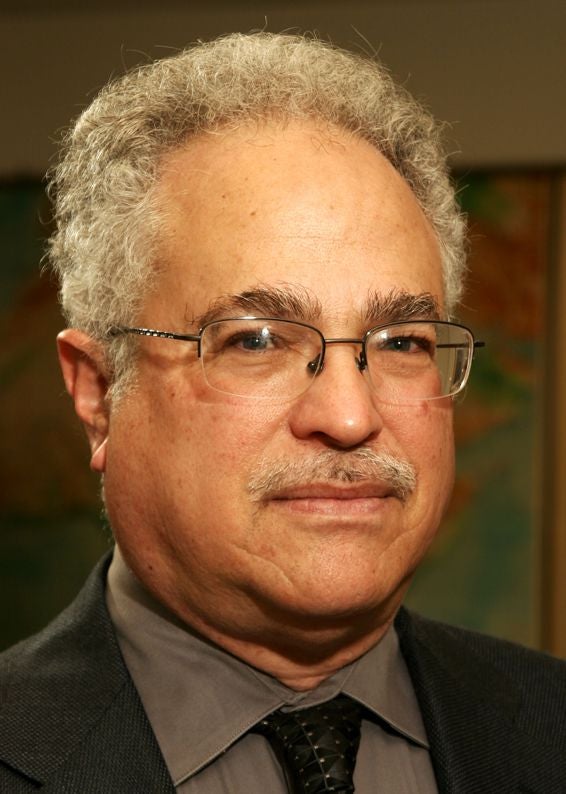

Two decades ago, a book by Black studies scholar and sociologist George Lipsitz fueled national discussions of race in America. Twenty years later, the conversation continues, and a new edition of the book, “The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit from Identity Politics,” highlights how far we as a country have come — and, more important, how far we have yet to go.

“In some ways the circumstances to be addressed have changed, and in some ways they’ve gotten better because there is a greater understanding of structural and institutional racism rather than merely private, personal and individual prejudice,” said Lipsitz, a professor of Black studies and of sociology at UC Santa Barbara.

“Much of the book’s argument was based on empirical data collected in the 1990’s, so people could say, ‘Well, that might have been true when this was put out two decades ago, but certainly things have progressed and these figures would look better today.’”

As Lipsitz points out, however, the education inequality, wealth gap, health gap and employment discrimination that linger long after — and despite — the Civil Rights Act and other legislation outlawing legal discrimination — paint a picture that in 2018 still looks bleak.

Where We Were and Where We Are

In this 20th anniversary edition, published by Temple University Press, Lipsitz offers, in addition to updated statistics, analyses of defining issues and events, including the nature of anti-immigrant mobilizations; police assaults on Black women; the killings of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Freddie Gray and others; the legacy of the Obama administration and the emergence of President Donald Trump; the Charlottesville mob action and killing of protester Heather Heyer and other hate crimes; and the ways in which white fragility, fear — and failure — are driving a new ethno-nationalism.

The book, he said, identifies ways in which power, property, and the politics of race in our society continue to contain unacknowledged and unacceptable allegiances to white supremacy.

“The default fallback position in this society is to blame people of color themselves and say they were unfit for freedom,” Lipsitz explained. “And that ignores all of the direct and second-, third- and fourth-generation indirect forms of discrimination, exclusion and subordination. My job, first of all, was to update the facts and figures to point to the fact that violent incidents like Dylann Roof walking into a church in Charleston and gunning down nine people is only the tip of the iceberg. Some 60,000 Black people die prematurely every year because of the stress caused by discrimination and by place-based impediments to medical care, healthy food and clean water and air.”

The Strength of the Black Freedom Tradition

But Lipsitz also is quick to point out that while much of the book is an indictment of racism and the mindset that allows it to flourish, its subtext is that the Black freedom tradition is alive and well, and not solely the provincial particular concern of Black people. Rather, it offers a path toward justice, a way of expanding democracy for everyone.

“This is the other side of America’s racial nightmare,” he explained, “that even in the face of this catastrophe, the Black freedom tradition has called to its side principled people of every background and every religion, every race, every gender identity and every sexual identification. Not everyone gives in, not everyone gives up, not everyone knuckles under. And in the face of this, I feel that there’s a mobilization constantly going on in this society.”

Lipsitz said he’s not surprised by the current state of politics and race relations in America. “Read W.E.B. Du Bois’s ‘Black Reconstruction in America’ talking about the 1860’s and 70’s. Read Ida B. Wells’s autobiography of her life from the 1860’s to the 1930’s — everything that’s happening today is in those books,” he noted. “It’s daunting to see how deeply rooted these practices are.

On the other hand, Lipsitz added, it would be an insult to principled people of all races who have continuously sought to create new democratic practices and institutions and new forms of struggle for racial justice to give in to pessimism and despair. “Part of what I tried to say in the introduction of the book is that I feel joyful in confronting some of these realities not because the problems have anything pleasant about them, but because it’s humbling and inspiring to see people organizing, mobilizing and engaging in litigation, legislation, organization and education around these issues,” he said.

The Role of Social Media

And how has social media impacted the situation? People fight with the tools they have in the arenas that are open to them, said Lipsitz. “The combination of mass media by corporations and multinational conglomerates leaves very little room for the average person to speak up and speak out, to be seen and to be heard,” he explained. “So social media was tremendously attractive to a lot of people who felt it gave a public space that took the place of what used to be done in trade unions, in community neighborhoods, and in political parties.”

Social media, he went on, created a whole new public sphere. “In some cases, as in the responses to Ferguson, to the killing of Michael Brown, no one really would have known about the incident if it hadn’t been for Black Twitter,” Lipsitz said. “The politicians didn’t speak up; the preachers didn’t speak up. But young Black people, using the one tool available to them, broadcast it all over the world.”

But visibility isn’t necessarily viability, according to Lipsitz, and social media has its downsides. Much of social media reflects the meanness, the mendacity the callousness and the cruelty of the broader society. “It’s no substitute for humble, friendly, reciprocal, deliberative dialogue among citizens. When anti-racism is at its best, it comes out of that.

“I don’t rule out any terrain,” he continued. “I think social media is important, but there’s no magic bullet, no technology, no leader, no generational change that’s going to do for us what we need to do for ourselves.”

The Scholarly Perspective

Lipsitz is the recipient of numerous honors and awards, including the American Studies Association’s most recent Carl Bode-Norman Holmes Pearson Prize for career distinction and that organization’s Angela Y. Davis Prize for Public Scholarship. Yet his research proceeds from the premise that scholarship needs to draw on the profound knowledge that emanates from aggrieved communities in struggle.

This edition of “The Possessive Investment in Whiteness” draws on Lipsitz’s 20 years of participation with the African American Policy Forum, the National Fair Housing Alliance, the Woodstock Institute and the New Orleans-based organization Students at the Center. “My point of entry has been fair housing, educational equality and economic and environmental justice,” he said, adding that there are longstanding and emerging forms of insight and critique all around us. “You look at the movements of indigenous people pointing out the continuing consequences of their dispossession and what it’s meant for the environment and for the nation, for example. The answers are all around us, just as the problems are all around us. And it’s up to us to listen to whoever talks and talk to whoever will listen.”

Becoming Agents of Change

So what’s the key to creating change? Action, Lipsitz said. “When asked about the secret of organizing, the great Ella Baker, who was Martin Luther King, Jr.’s secretary with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and later the guiding adult force behind the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, said, ‘Find somebody who’s doing something and help them.’

“And I believe that,” he added. “You can’t invent a solution in your office or at the library or at your computer. You have to put on your shoes and go out and find people who are doing things. This is how abolition democracy came about in the 1860’s and 70’s. This is how democratic and egalitarian movements of the 1960’s and 70’s happened. When things change, it’s because ordinary people find a way to make things happen.”