Education on Exhibit

In the late 1800s, a new method of education started taking hold in the U.S. Inspired by early Russian educational techniques and founded in Scandinavia, Sloyd, as the method was known, emphasized manual training, linked closely to European folk art traditions and the emerging Arts and Crafts movement.

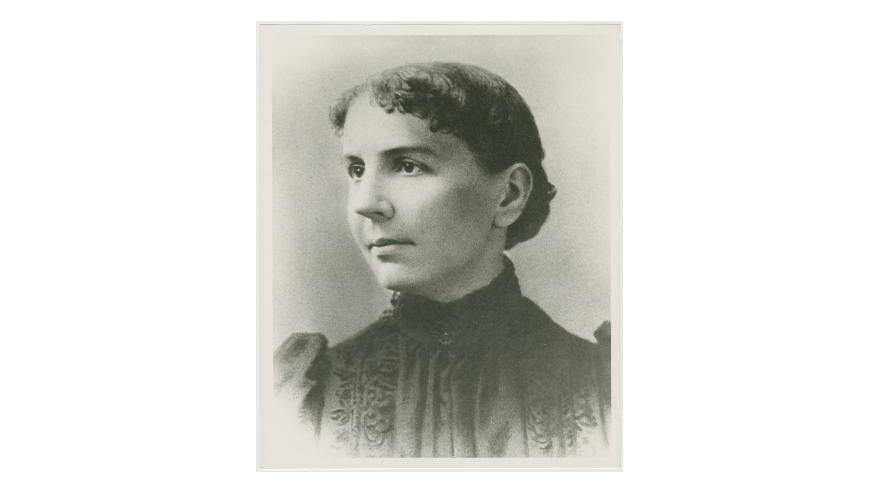

One pioneering educator, Anna S.C. Blake, brought Sloyd to Santa Barbara. And the school she founded can today be traced forward through time — if by dotted line — to UC Santa Barbara. A new exhibition, open now through Dec. 20 in the Library Mountain Gallery, explores this fascinating history. Admission is free and open to the public.

“For me, the significance of Anna Blake is how a dedicated individual, working with others, can build a school that would eventually become one of the world’s great research universities,” said John Majewski, the Michael Douglas Dean of Humanities and Fine Arts. “It is a lesson of how the institutions we create in our own lifetimes can reverberate, in completely unexpected ways, more than a century later. The values that defined Anna Blake — a commitment to public service, innovative teaching and learning, and widespread access to education — continue to shape the identity of UC Santa Barbara.”

Motivated by a Progressive Era belief that all students should have access to a holistic education emphasizing both intellectual and practical knowledge, Blake in 1892 founded the Santa Barbara Sloyd School, basing its curriculum on the method. Students learned by doing, and they started young. It was the first school in the country to bring Sloyd into kindergarten.

So were planted the first seeds in the educational family tree that would eventually sprout the State Normal School of Manual Arts and Home Economics, then Santa Barbara State Teachers College and, still later, UC Santa Barbara. Pushing boundaries, it seems, is deep in the roots.

The new exhibition, curated by Sarah Case, a continuing lecturer in history, and history graduate student Norah Kassner, highlights the Anna S.C. Blake Memorial School — it was renamed for her following her death — examining how Santa Barbara reformers thought about the intersection of education, the manual arts and social mobility in the 1890s, and the implications of those beliefs on higher education today.

“During the Progressive Era is when new approaches to education associated with Maria Montessori, John Dewey and other people emerge,” said Case, who also is managing editor of academic journal The Public Historian. “Anna Blake was very much of her time in emphasizing hands-on education, experimental education and the use of physical objects as a way to learn. She also was part of the growth of California, especially in Santa Barbara, and the growth of the city, attempts to beautify it and regulate some city growth — and that’s part of her story as well.”

According to Case, the exhibit has the potential to illuminate these broader stories of the Progressive Era and the development of Santa Barbara, including attitudes toward education and citizenship, local arts, the gendering of Progressive reform, race and class in early 20th century Santa Barbara, and the rise and fall of manual education.

“In many ways Anna Blake was typical of Progressive Era educators,” she noted. “She was born Boston, then she comes to Santa Barbara and brings current thinking about education and becomes influential here. She was very much a part of the growth and expansion in education around the turn of the 20th century that understood manual training as a way to enhance education for all students and as a means of teaching character as well as skill. Her school included both boys and girls, both Spanish speakers and English speakers.”

In the school’s early years, younger children learned the same skills. Older students took academic courses together, but manual arts courses were gendered, with girls studying sewing and cooking while boys pursued woodworking. Remarkably, one report noted a number of girls in the carpentry courses, but generally the Sloyd courses were sex-specific.

Ednah Rich, the head of the school who was hand-picked and paid by Blake, paved the way for its evolution. A prominent education advocate, she pushed hard for its next iteration as a training school for teachers of manual education. And she succeeded.

Absorbing the Blake School, the California State Normal School of Manual Arts and Home Economics was founded in 1909. It was the first school of its kind in the country, and Ednah Rich, as director, was then the only woman in the U.S. to serve as president of a state normal school. Locally prominent graduates of the teacher training institution included Pearl Chase, who in 1912 completed her degree in domestic arts.

Rich and Santa Barbara officials soon went looking for a new location, where the school could expand its footprint — both literally and figuratively — and make it feel more like a home than an institution. They settled on a site on Mission Ridge and embraced the city’s emerging bent toward Spanish-style architecture. The Riviera campus was born.

The Normal School in 1921 was renamed Santa Barbara State Teachers College, as curriculum started shifting toward liberal arts and four-year degrees were introduced. The institution was incorporated into the University of California in 1944 and relocated to its current oceanfront home a decade later.