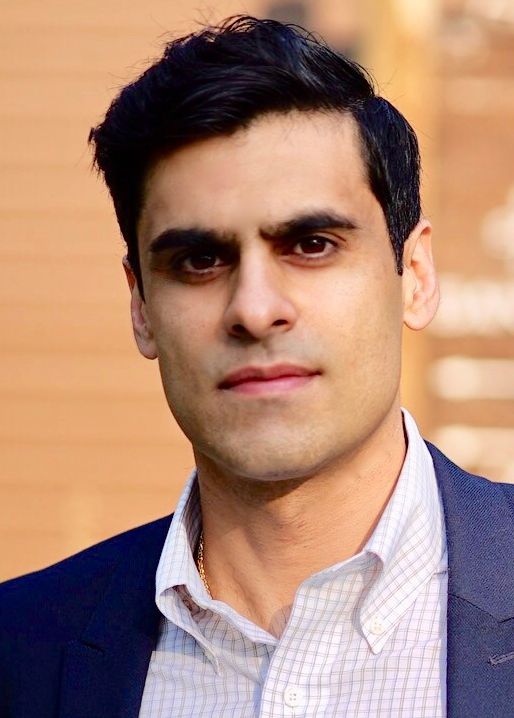

Summit Briefing

Threats to national security are not purely academic to Neil Narang. A UC Santa Barbara assistant professor of political science, in 2016-17 he advised senior officials in the Department of Defense while on an International Affairs Fellowship, focusing on national security strategy. During his appointment, Narang served as a senior advisor in the Office of the Secretary of Defense for Policy in Strategy, Plans and Capabilities. As part of the office’s strategy team, he worked on assessing risk across a range of global threats. It was an assignment that he was particularly qualified to do.

Now, as President Trump prepares to attend a summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un, The Current asked Narang about the national security implications of talks with the North.

The Current: Former President Obama is said to have told President Trump that his biggest national security challenge would be North Korea. Can you summarize why that would be?

Neil Narang: I can’t say whether or not North Korea is — by any objective measure — the biggest national security challenge, but it certainly seems to be among the most serious and most complex. There are several reasons for this assessment.

First, North Korea is a nuclear weapons aspirant. After decades of nuclear weapons pursuit that resulted in a series of nuclear detonations, North Korea successfully test-launched two Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) with sufficient range to strike the continental United States. Despite doubts over whether they have mastered the key elements of delivering a nuclear-tipped ICBM, foreign policy analysts regard the new capability as a critical milestone.

Second, many non-military tools for imposing costs on the North Korean regime, like economic sanctions, appear to have failed in halting the progress of their nuclear weapons program.

Third, any military option designed to slow down the North Korean nuclear weapons program would be uniquely challenging to carry out. The North Korean military currently holds a tremendous amount of value at risk (i.e. hostage), both in terms of human lives and physical infrastructure. Within hours of any attack, tens of thousands of American lives on the Korean Peninsula and hundreds of thousands of Korean lives could be lost from conventional retaliatory strikes alone (leaving aside the possibility of a successful nuclear strike), and this doesn’t count the many billions of dollars in physical damage to infrastructure. To quote the current Secretary of Defense James Mattis, such a conflict in North Korea “would be probably the worst kind of fighting in most people’s lifetimes.”

Finally, to make matters more complicated, China — perhaps the fastest rising global power — has an unclear level of involvement in and over North Korea. Thus, any conflict with North Korea presents some risk of a broader regional dispute.

And these are only four reasons, among dozens, that make the North Korean crisis uniquely challenging.

TC: What would it take for North Korea to be considered a non-national security threat?

NN: This is a tough question, because it depends on who you ask. Foreign policy makers vary in their assessments of risk and their threshold for taking costly actions to mitigate risk. For example, the Clinton administration and Bush administrations had very similar information about the Iraqi WMD program, but very different policies that followed.

Such is the case with North Korea. At one extreme, there are probably those who will consider North Korea a threat until their preferences are more fully aligned with those of the West, even if there is a freeze in their nuclear weapons program. Others might accept a North Korea with unaligned preferences, as long as they reverse their nuclear program.

That said, foreign policymakers that I know typically don’t see the threat posed by countries in a binary way: threat vs. non-threat. Rather, they have a more continuous understanding of threat where countries are more or less threatening to U.S. national security compared to other countries, and more or less threatening over time. In this way, the more relevant question is not what it will take for North Korea to no longer be considered a national security threat, but instead what is the optimal allocation of our scarce defensive resources across the various potential threats — of which North Korea is only one.

TC: As someone who’s studied the role of technology in national security, what concerns you most about North Korea, other than the obvious nukes?

NN: This may be an odd answer, but I am most concerned about the role of technology in resolving uncertainty between the U.S. and North Korea. In many ways, crises like the one between the U.S. and North Korea all have a familiar dynamic: each side attempts to communicate their capabilities and resolve by sending progressively costlier signals that less capable and less resolved states would be unwilling or unable to send. However, in such situations, there is always the chance for misperceptions and miscalculations on the way up the “escalation ladder.”

In this game of brinkmanship, my fear is that one side takes actions that are meant to be either benign or only marginally escalatory, but that the other side misperceives these incremental escalations (or even non-escalations) to be a precursor to a conventional or nuclear strike and then disproportionality responds. Since sides cannot always trust each other to communicate their true intentions at the bargaining table, these beliefs end up being influenced by technologies related to intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR), along with the human systems designed to interact and interpret the data generated by these systems. I am concerned not only that these systems may not be perfectly reliable, but that sides don’t have a complete understanding of each other’s limits.

TC: Best-case scenario for talks? Worst?

NN: The worst-case scenario in the near term is that talks ultimately fail to end in a negotiated settlement. To date, much attention has been paid to the risk and dramatic consequences of nuclear war in the event of failed negotiations, but many believe that the likelihood and the consequences of a conventional war would be equally bad, if not worse.

The best-case scenario would be an expedient settlement of the stakes.

I suspect that the most likely outcome is something in between: a partial resolution of some of the issues at stake, alongside continuing provocations and acts of risk-taking to signal the resolve to fight over other issues that cannot be settled in the near term. In this way, negotiations will almost certainly go on for years (if not decades), albeit at lower levels of escalation and visibility that escapes the attention of most people.

TC: North Korea said it had dropped its demand that the U.S. withdraw its troops from the Korean Peninsula. Mainstream media make it sound like a breakthrough, but North Korea has done this before. Big deal or posturing?

NN: In any bargaining situation, sides often have the incentive to make maximal demands to in order to set the bargaining range in their favor, and fully anticipate that the eventual settlement will fall somewhere between the status quo and their maximal demands. Given this incentive, it is difficult to know whether the North Korean leadership every truly expected the U.S. to withdraw troops from the Korean Peninsula, or if the initial demand was made in an effort to improve the settlement that is ultimately agreed upon by both sides.

TC: Anything you’d care to add?

NN: I would add two points. First, there is a natural tendency to imagine and privilege military solutions to the current crisis with North Korea. In many ways this is understandable. However, it is important to remember that there is now, and there has long-been, non-military options through which the international community might impose significant costs in an effort to bring the North Korean leadership to the bargaining table (economic sanctions, diplomatic isolation, etc.). Of course, it can be reasonably argued that many of these options have been exhausted along the way to the current situation, wherein the North Korean nuclear program has advanced significantly and North Korean leadership has become increasingly revisionist. However, the point remains that there are many different foreign policy tools, which can together combine to form many different policies, through which the international community might achieve desired concessions from North Korea.

This leads to a second and related point. The position (and the power) of the United States in the world today and into the future is likely more than a strict function of its military capabilities. It is also a function of the alliances it maintains, the moral standing of the policies it pursues, and many other non-military factors. This is important because there may be policies that the U.S. could pursue to maximize U.S. national security interests in the short term, which might nevertheless diminish U.S. standing (and possibly national security) in the long term. That is, some strategies might be effective at extracting favorable concessions from the Kim Jong Un regime but might only function after imposing unacceptably high costs on ordinary citizens, much like the Oil-for-Food Program did in Iraq. The point is that there are moral and humanitarian considerations that may have long-term implications for the position (and the power) of the United States in the world that shouldn’t be ignored.