‘Starving for Justice’

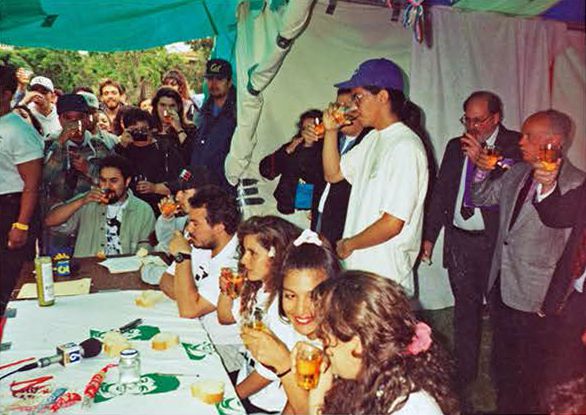

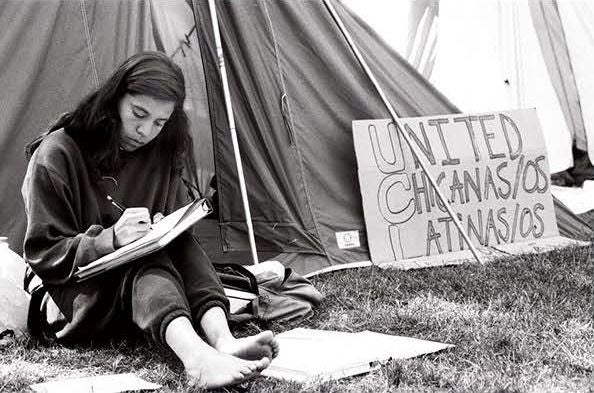

In 1993 and ’94, groups of Latino students staged hunger strikes on three California university campuses: UC Santa Barbara, UCLA and Stanford. They demanded, in part, that the schools form or expand Chicano studies programs at a time when the state was roiled by anti-immigrant sentiment and a ballot proposition that sought to deny essential public services to undocumented immigrants.

The hunger strikes have largely faded from public memory, but UCSB scholar Ralph Armbruster-Sandoval has published “Starving for Justice: Hunger Strikes, Spectacular Speech and the Struggle for Dignity” (The University of Arizona Press, 2017), the first in-depth examination of the protests.

Each hunger strike, Armbruster-Sandoval said, “had its own story to tell.” At UCLA, where the fasting lasted from May 25 to June 6, 1993, protesters demanded the university create a Chicano studies department. At Stanford, a combination of factors — including racial tensions and the lack of a Chicano studies department — led four Latinas to strike May 4-7, 1994.

At UCSB, which established the first Chicano studies department in the UC system in 1970, nine students staged a hunger strike from April 27 to May 5, 1994. They demanded that the university expand the department from three full-time faculty members to 15 and establish a Ph.D. program. They also wanted grapes banned on campus (the United Farm Workers were leading a grapes boycott), a community center, fees rolled back and greater diversity on campus.

Armbruster-Sandoval, an associate professor of Chicana and Chicano studies at UCSB, explained that many Latino students on campus believed the Chicano studies department had been neglected by the university. After a quarter of a century the department essentially had the same number of full-time faculty as when it started. “Twenty-five years later, a lot of students were saying, ‘We thought we had movement, we thought we were doing some great stuff with a lot of big victories, but 25 years have passed and what do we have to show for it?’ ”

The students’ frustrations were exacerbated by a political climate that seemed hostile to Latinos, Armbruster-Sandoval said. Proposition 187, championed by then Gov. Pete Wilson, was written to deny undocumented immigrants public social services such as education and health care. It passed by 18 percentage points in November 1994 — although it was later ruled unconstitutional and never implemented. That same year, the U.S. Border Patrol implemented Operation Gatekeeper, which critics maintained militarized the U.S.-Mexican border to stop migration from Mexico.

“It kind of felt like they were at war,” Armbruster-Sandoval said. “It seems dramatic to say, but that’s what it seemed like.”

In the end, all three hunger strikes produced results, even if they weren’t immediate. Today UCLA boasts the César E. Chávez Department of Chicana and Chicano Studies, with 16 faculty members, more than 450 undergraduate students and roughly 30 Ph.D. candidates. Stanford eventually established the Center for Comparative Studies in Race & Ethnicity, which houses the Chicana/o-Latina/o Studies Program.

At UCSB, the Department of Chicana and Chicano Studies today has 11 faculty members and a Ph.D. program that has seen many of its graduates obtain tenure-track positions across the country. The university is a designated Hispanic Serving Institution; roughly a quarter of the campus’s undergraduates are Latino, up from just 10 percent in 1994.

Armbruster-Sandoval believes that the hunger strikers achieved something that can’t be measured. “In these protests, students wanted something real, something you could touch and obtain, but they also wanted something elusive and almost mystical,” he said. “César Chávez often talked about dignity, and in these protests, which borrowed from his tactical tool kit, these students wanted that, too — dignity for all people in a world and university which was becoming ever more undignified. The students wanted to be treated as real human beings. I think that they successfully did that, but of course new struggles for dignity are necessary today given the political climate that exists right now.”

Armbruster-Sandoval even argues he owes his job to UCSB’s hunger strikers. “Had it not been for the strike opening up the space to get more hires, I simply wouldn’t have been hired,” he said. “In other words, I owe my livelihood to the strike.”