‘Downwardly Global’

In a drab, windowless room in Toronto, Lalaie Ameeriar listened as a woman told a group of South Asian immigrants, all women, how to find a job in Canada: Don’t smell like foreign food; change your name if it’s hard to pronounce; don’t wear traditional clothes or a hijab.

The advice seemed stunningly odd to Ameeriar, an assistant professor of Asian American studies at UC Santa Barbara. The women were educated professionals eager to work in their fields, but the Canadian government appeared to have little for them but tips on erasing their foreignness so that they might fit in.

“Honestly, the first time in a workshop when someone said, ‘Don’t show up smelling like foreign food,’ that was pretty shocking to me,” Ameeriar recalled. “And because it was so shocking and ended up happening so many times, it became the basis of what I was doing.”

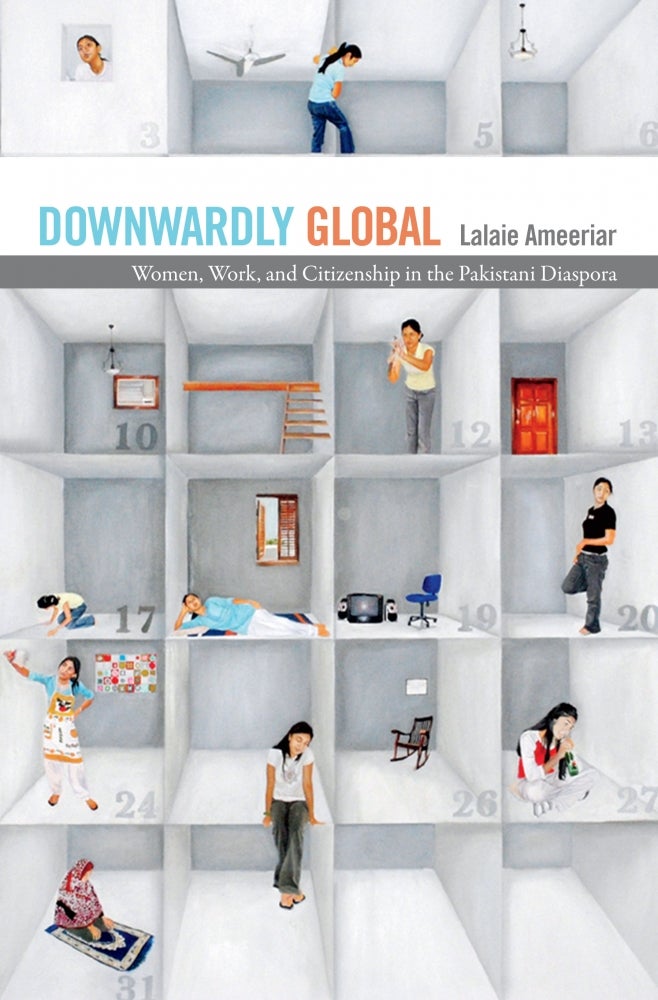

What she was doing was research that became a book, “Downwardly Global: Women, Work and Citizenship in the Pakistani Diaspora” (Duke University Press, 2017), that examines the plight of professional Pakistani women who emigrate to Canada only to find unemployment and poverty.

Indeed, 44 percent of Pakistanis in Toronto live below the poverty line, and most of those “skilled workers” will never work in their fields again, Ameeriar found. They end up in low-paying “survival” jobs in retail and service work. Some professional workers who Ameeriar spoke to wondered, “Why does the Canadian immigration system favor these skilled professionals, and yet not create opportunities for them on the ground?”

To answer that question, Ameeriar explored the role of globalization and Canada’s unique sense of multiculturalism. The latter, she found, is freighted with contradictions that fall especially hard on Pakistani women. Canadians, especially those in Toronto, regard their multiculturalism as enlightened, Ameeriar explained, and highlight it with festivals that celebrate the sights, sounds, tastes and smells of South Asia.

And yet Canadian society demands of its South Asian immigrants what Ameeriar calls a “sanitized sensorium” — the erasure of the “Otherness” that makes them unique. “Because of the politics of multiculturalism, there’s this interest in producing a sense that it’s more inclusive,” she said. “Part of that is about these multicultural festivals that produce sensorial phenomena in the form of clothing and smells and bodily adornments that show Canada’s inclusive. But it doesn’t translate into economic integration.”

The impoverishment of Pakistanis in Canada is something Ameeriar knows intimately. Her mother was a teacher who emigrated, but was unable to work in her field.

“I grew up in Canada; I grew up in Toronto, and Canada has this kind of presumed multiculturalism in contrast to the United States,” she said. “So when you grow up in Toronto, the rhetoric is, ‘We’re better than the U.S. because we’re so inclusive.’ And so to be faced so starkly with this kind of performance was shocking to me, having grown up as an immigrant subject.”

This paradox of culture celebrated and suppressed is particularly hard on women, Ameeriar said. Globalization opens the door for them, but the failures of multiculturalism leave them vulnerable to racism, both overt and unintended.

“While I was growing up in Toronto I didn’t think about it in terms of race,” Ameeriar said. “It was just hard luck or something. But seeing it in a sustained way, happening to so many people, made me rethink the way that multiculturalism is practiced.”