A Pioneering Netizen

At first blush, Alan Liu, a distinguished professor of English at UC Santa Barbara, would seem to be an unlikely pioneer of the internet. He was a scholar of British Romantic poetry, an analog art centuries removed from the coming digital revolution. But seeing the internet’s potential, he dove in.

“I was here at the very beginning of the World Wide Web,” Liu said. “I was very early on learning HTML and so on, which was fairly unusual in those days in the humanities departments.”

Since 1994, when he created Voice of the Shuttle (VoS), a “Website for humanities research,” Liu has been a leading proponent of incorporating the digital world into the humanities. It’s been a period of technological leaps forward and malicious setbacks, and Liu will recount it in the talk “ ‘Wild Surmise’: How Humanists and Artists Discovered the Internet at UCSB, c. 1994 — An Origins Story,” Friday, Jan. 13, at 10 a.m. in the UCSB Library Instruction & Training Room 1312. It is free and open to the public.

A hand-coded collection of links to online resources in the humanities, VoS was what Liu calls the “good hack” — a product of ingenuity and resourcefulness. “You have to remember in the early days of computing,” he explained, “before we had our elaborate software and control interfaces, running a computer meant you took a wire out of this socket and you moved it over here to program the machine to do what you wanted to do. That kind of hacking, in the sense of a workaround solution, has long been part of the mindset of computing.”

In curating VoS, Liu focused on the ontology of data — cataloging and classifying information in a way that made it accessible to humanities scholars. “Part of what I put in place in VoS was not just a pile of links but a framework, a set of categories and way of thinking through the relationship between categories that I carefully annotated,” he noted. “And that remains of value. It’s really hard to recover that kind of ontology without someone who knows the field or fields and is thinking through the relationship between them.”

Maintaining, or “weaving” VoS — the name alludes to the myth of Philomena, who wove a tapestry that told of her rape and mutilation by her brother-in-law — was initially a labor of love. “I spent about two hours each night just having fun, finding things I thought would interest scholars and putting them on my page,” Liu recalled. “It was a lot of fun back then, just every night going out and just seeing new things.”

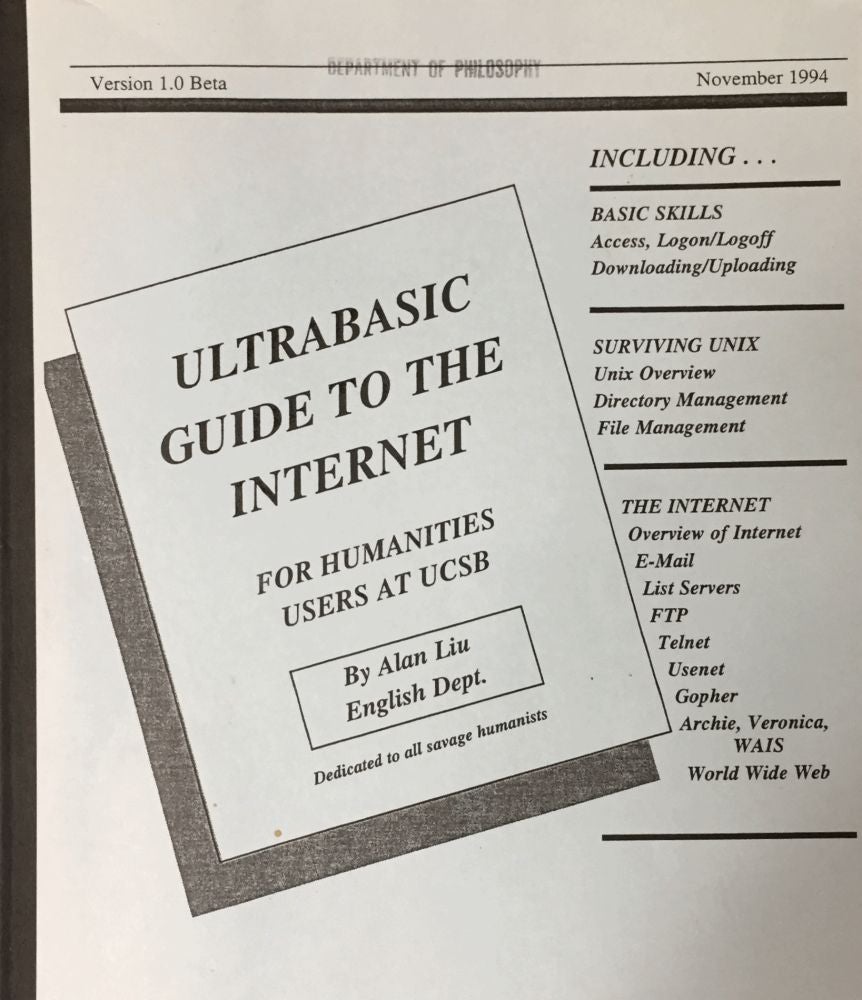

Liu even wrote a book, “Ultrabasic Guide to the Internet: For Humanities Users at UCSB,” that was sold through the campus bookstore. He made “maybe $60” on it. But he wasn’t in it for the money. “Back then I thought I could edit the internet,” he said. “Many of us did. In my mind my competitor at that time was the original Yahoo, which was a hand-curated list of things before they became a search engine in the Google philosophy of things.”

And then came “the bad hack.” Trolls and bad actors are not new phenomena on the internet. Seven years after creating VoS, “I woke up one morning and there was nothing left” of the site, Liu said. “They had come in and removed all the tables and all the content and so on. They just left a comment, ‘Bad hack.’ ” He rebuilt it as a database with more robust security.

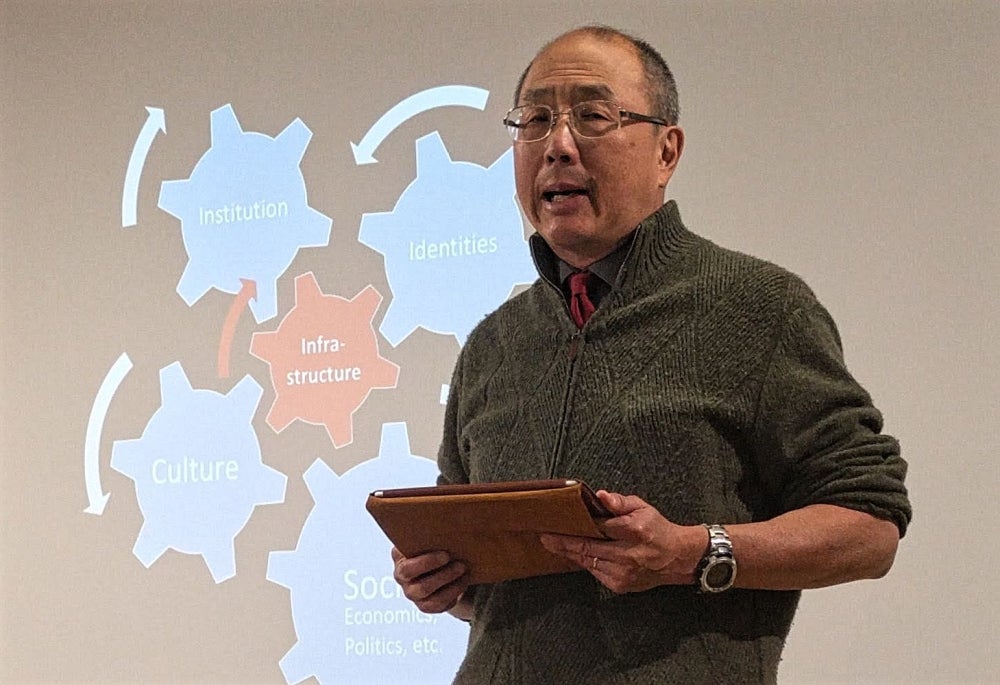

Today, Liu is deeply involved in the digital humanities — engaging the internet to get a better understanding of the humanities. He likens it to Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press, around 1440, in what is now Germany. Gutenberg, he said, didn’t just invent moveable type and the press, he created a whole system that worked to revolutionize the distribution of information. “He was curious and interested in the nature of ink, the nature of the platens that went into the press,” Liu noted. “He was interested in the whole series of moving parts that came together in what we know as the printing press today.”

In the same way, Liu says, today’s humanities scholar must understand how the internet works. In his classes he requires students to “get under the hood” of the internet by using some tool — some simple coding, for example — as a tactical exercise. “If you think about it,” he said, “it is completely insane that any humanist today would not be interested in the entire system of the internet, which is our version of the printing press, in the same way Gutenberg was interested in the system back then.”