Giving Credit Where Credit is Due

Solving today’s environmental problems involves vast amounts of data, which have to be gathered, stored, retrieved, analyzed and — increasingly — cited in academic journals. That last step, however, presents a problem.

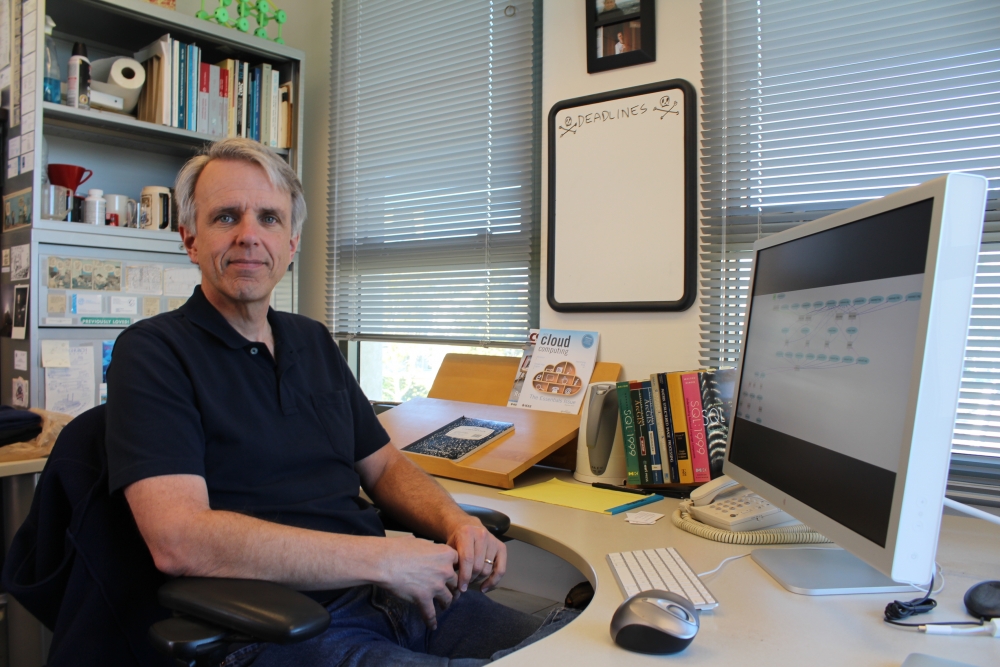

“For purposes of honesty and reproducibility, academic publishers are very rapidly moving toward requiring those who publish an article to also publish the data backing it up,” said James Frew, an associate professor in UC Santa Barbara’s Bren School of Environmental Science & Management, and an expert on data storage and provenance. “It’s happening now and is going to affect everybody.”

In a new paper, Frew and colleagues from the University of Edinburgh and the University of Pennsylvania offer a solution whereby citations would be generated automatically. The team’s findings appear in Communications of the ACM, the leading publication of the Association for Computing Machinery.

Citations have the important role of directing readers to supporting information and giving credit where credit is due. While different fields and journals have their own specific citation rules, most are variations on a simple, universally accepted standard. That system has worked well for decades, as long as cited materials were fixed, unchanging objects like books or articles, but it doesn’t transfer to data.

Increasingly, scientific data is stored in large databases with incredibly complex structures and are accessible via the web. While some databases, like those containing election results, are static, others, which may contain yearly demographic data or climatological data from satellites, grow and change over time.

An example is the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis, where working groups create huge data sets by combining smaller sets from multiple researchers. When that data is cited, both the database and the person who originally gathered the data should be included in the citation. However, currently, even if scholars want to cite the sources of data they use, they may not be able to, because no standard tool exists for generating database citations.

“We get one of two extremes in database citation,” Frew said. “Either we get a citation to the complete database package or to a piece of information where the citation is so granular it cannot be connected back to the original data set.” Sometimes a citation is lacking altogether.

Frew and his colleagues describe a system within the database that would automatically generate a citation in a standardized format whenever data is extracted from a database. They suggest that by using the same computing power that makes databases possible, database citations can be made more specific while also accurately accounting for all data authors.

According to Frew, this responsibility will fall to database managers, who would need to take three steps: Define the various ways their data can be queried or “viewed,” create citation templates for the standard set of views and provide a computational mechanism to allow researchers to generate citations for specific queries.

Frew and his team outline a solution and demonstrate its versatility by applying it to two different scientific databases that he described as being “radically different in both their structure and how they should be cited.” Their suggestions lay a foundation for expanding the kinds of citations available to the academic world and offer improvements to database citation by combining computational power with the foresight of database managers.

“My hope is that our suggestions for automating citations will encourage managers to implement similar systems and make it easier for those using the data to cite it appropriately,” Frew said.