Emotional Education

Call them “internal events.” Thomas Scheff does.

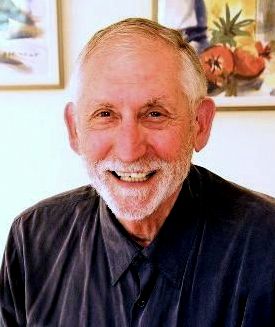

The UC Santa Barbara sociologist considers the phrase an apt descriptor for emotions, those intangible queues working as “signals that alert us to the state of the world inside and around us.” And in a recently published paper, Scheff suggests that school curricula should include instruction in navigating those “events” at an early age.

Appearing in the journal Medical Sciences, Scheff’s new piece, “An (Emotion) Problem in Cooperative Education,” makes a case for more comprehensive emotional education beginning in elementary school classrooms. Helping kids to learn and talk about emotions, he argues, will in turn provide them the tools to better understand and manage their feelings over time.

Few things are so important, argues Scheff. Acknowledging the popular movement toward social-emotional education for K-12 students, he contends that while the social portion appears to be succeeding, the emotional component is still lacking.

“The emotion world is a big mess in modern society because we haven’t really defined what we mean by the different emotions,” Scheff, an emeritus professor of sociology, said in an interview. “Emotions are defined one by another. Anger is a kind of rage. Well, what is rage then? Everything is ambiguous and unclear.

“It’s extremely important — and I’m particularly interested in starting early, in kindergarten — because I think our children need to get introduced to emotions in a different way,” he continued. “To withdraw and ignore is what many people do to deal with emotions, but you can also hide one emotion behind another. In cases where one learns to hide shame behind anger and aggression, for example, that can actually turn out to be extremely dangerous.”

After spending many years studying the stigma of mental illness, Scheff has devoted the second half of his career to research on emotions and the impact of lingering taboos around owning our emotions and calling them by name. His work has examined the destructive nature of shame and its role in anger and aggression and our cultural proclivity to dismiss emotions as mere “feelings,” rather than recognize them as the physiological occurrences that they are. Scheff has also documented the detriment to scholarship when researchers study shame, but don’t use the term itself.

In his new work, Scheff offers a provisional way to begin adding emotion components to K-12 cooperative teaching, based on descriptions of each of six emotions: grief, fear, anger, pride, shame and excessive fatigue.

“In modern societies, understanding emotions is beset by an elemental difficulty: the meaning of words that refer to emotion are so confused that we hardly know what we are talking about,” he writes. “When compared to beliefs and actual studies about behavior, thoughts, attitudes, perception and the material world, the realm of emotions is still terra incognita. A common assumption is that emotions are unimportant, yet they may play a key role in the behaviors of individuals and even of nations.”

Beginning to address that gap, Scheff said, could be as easy as giving kids a simple prompt: “Tell me about some of your best moments.”

“I’ve done this in seminars at the university, where I’d start them talking about the best moments in their lives and not only do they laugh, but they also sometimes cry, and they like it,” Scheff said. “There is a way of approaching young people with emotions without scaring them to death and it involves getting the positive parts of their lives so that they will eventually talk about the more difficult things. It often turns out that some emotion being ignored or hidden is what’s causing the difficulty.

“There is a way of teaching emotions,” he added, “and I think it’s necessary for our personal lives, as a mass, as a nation, to start working on it.”