The Next Generation

Deep in the hills of South Dakota, scientists are poised to build the world’s most sensitive dark matter detector, known as LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ).

Named for the merger of two completed dark matter detection experiments — the United States-based Large Underground Xenon (LUX) and the United Kingdom-based ZonEd Proportional scintillation in Liquid Noble gases (ZEPLIN) — LZ will be at least 100 times more sensitive than its predecessor. LUX, a smaller liquid xenon-based underground experiment at the Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF) in Lead, South Dakota, is now being dismantled to make way for the new project.

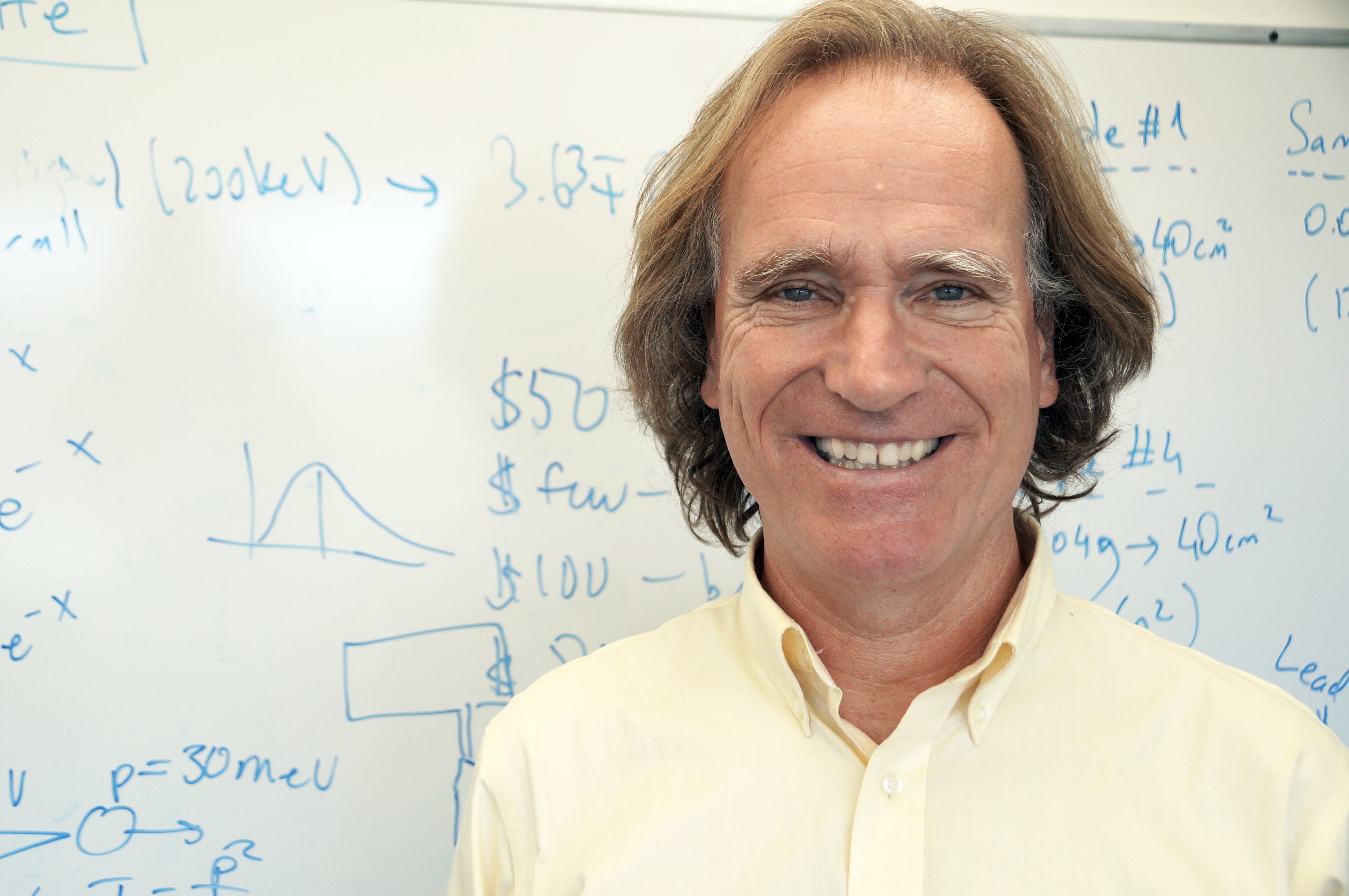

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) recently approved the LZ project’s overall scope, cost and schedule. According to UC Santa Barbara physicist and LZ spokesperson Harry Nelson, that has set in motion the building of major components required for the deep-underground hunt for theoretical particles known as WIMPs, or weakly interacting massive particles. Scheduled to commence collecting data in 2020, the experiment is designed to tease out dark matter signals from within a chamber filled with 10 metric tons of purified liquid xenon, one of the rarest elements on Earth. The project is supported by a worldwide collaboration of more than 30 institutions and approximately 200 scientists.

“The nature of the dark matter, which comprises 85 percent of all matter in the universe, is one of the most perplexing mysteries in all of contemporary science,” said Nelson. “Just as science has elucidated the nature of familiar matter — from the periodic table of elements to subatomic particles, including the recently discovered Higgs boson — the LZ project will lead science in testing one of the most attractive hypotheses for the nature of the dark matter.”

The mile-deep SURF site shields the experiment from many particle types that are constantly showering the Earth’s surface and would obscure the signals LZ is seeking. Although experiments seeking traces of dark matter have grown increasingly sensitive in the past decade, no interactions have yet been conclusively observed.

One of the first WIMP experiments, using detectors fabricated from germanium, was undertaken by professors David Caldwell and Michael Witherell in the 1980s. Since that time, innovation and new technologies have enabled experiments that are now a million times more sensitive than that pioneering work.

LZ will utilize liquid xenon to extend WIMP sensitivity another factor of 100. Liquid xenon was selected because it can be ultra-purified, including the removal of traces of radioactivity that could interfere with particle signals, and because it produces particular light and electrical pulses when it interacts with WIMPs.

LZ is designed so that a dark matter particle would produce a prompt flash of light followed by a second flash when the electrons produced in the liquid xenon chamber drift to its top. The light pulses picked up by a series of about 500 light-amplifying sensors that line the walls of the liquid xenon tank will carry the telltale fingerprint of the particles that created them.

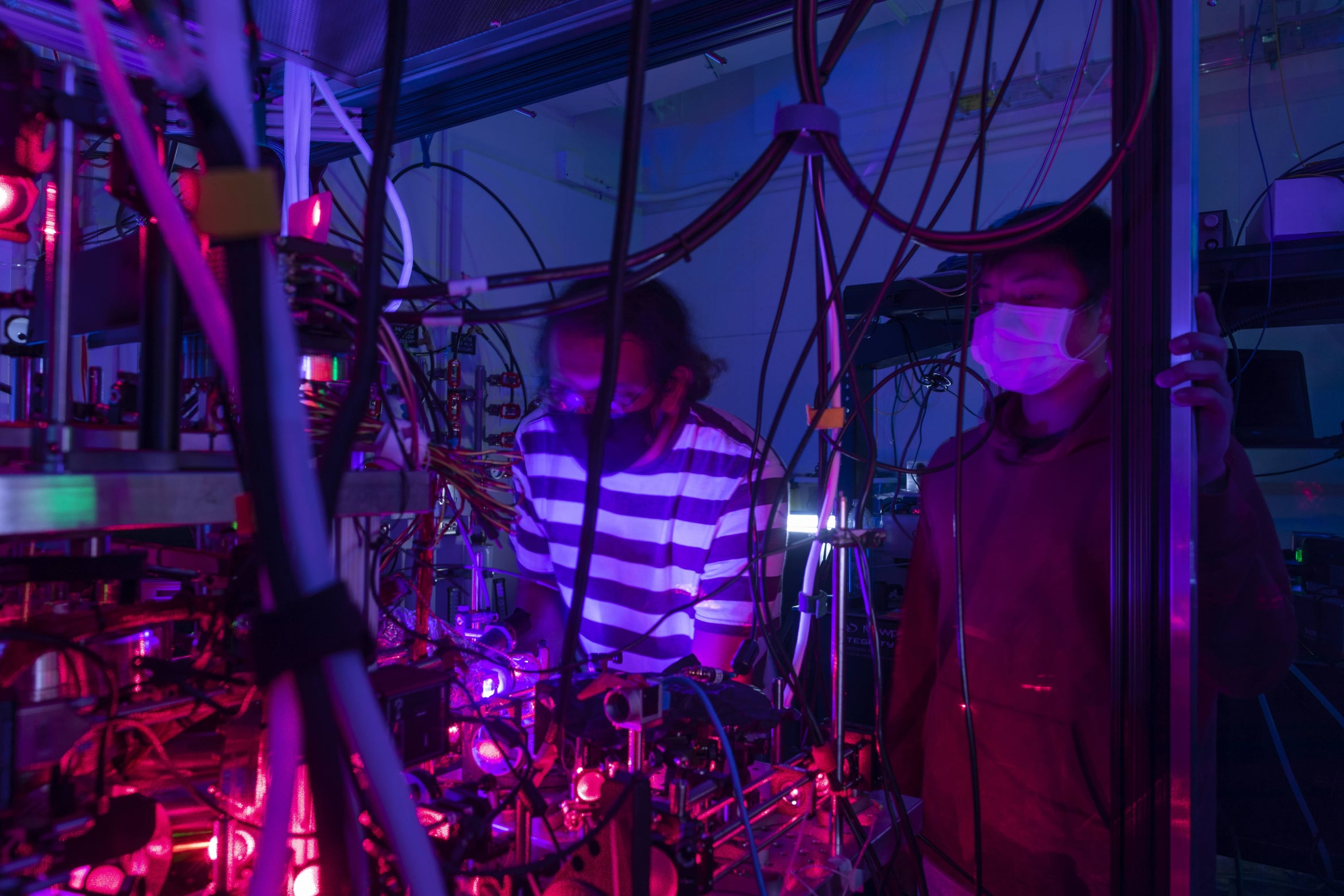

UC Santa Barbara is responsible for the detector system, known as the outer detector, which surrounds the liquid xenon tank. The outer detector permits the identification of a variety of signals that could fake a WIMP event. Graduate student Scott Haselschwardt and engineers Susanne Kyre and Dean White will deploy a prototype of the outer detector this November at SURF in South Dakota.

LZ is supported by the DOE’s Office of High Energy Physics (HEP), the U.K. Science and Technology Facilities Council, the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, the South Dakota State Legislature, and the South Dakota Science and Technology Authority (SDSTA), which developed the SURF. SURF is operated by the SDSTA under a contract with the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory for the DOE’s HEP. UC Santa Barbara has also provided substantial support for LZ.