A Body of Emotions

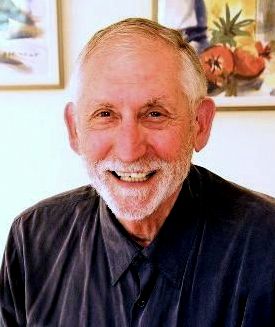

The study of emotions is a tricky business. Everybody experiences them, but even defining them is a fraught undertaking. “Experts disagree on almost everything about emotions,” said Thomas Scheff, emeritus professor of sociology at UC Santa Barbara.

Scheff, who has studied emotions for more than 40 years, tries to bring some cohesion to the topic in a new paper, “What Are Emotions? A Physical Theory,” published in the Review of General Psychology. Building on the work of researchers John Dewey, Nina Bull and others, Scheff holds that emotions are physiological responses to stimuli that have been delayed. Grief, for example, is stimulated by loss and prepares the body for a “good” cry of sobbing and tears that ameliorates the pain of the loss.

The other emotions — fear, anger, shame and what he calls “extreme fatigue,” or efatigue — are all physiological as well, Scheff said, and not what society accepts as mere “feelings.” Fear isn’t just feeling frightened, he explained, but the response to physical danger that prepares the body for shaking and sweating.

“The point of that paper is there’s a vast structure of emotional superstitions, basically, which people believe and take for granted, and it’s very hard to get beyond that,” Scheff observed. “They have to acknowledge that emotions must be in the body and not just feelings, and that’s a very hard move for most people. Sometimes it takes them years to even grapple with it, because they assume that an emotion is a feeling.”

Scheff’s work in emotions is both academic and personal. Beyond the copious research he’s done over the decades, he explained that his own experiences with emotions have given him invaluable insight. In the paper he recounted an episode of extreme fear during a period of on-campus demonstrations against the Vietnam War.

One day, when he was scheduled to speak at a demonstration, an anonymous caller told Scheff that he would kill the professor and his family. Recalling a self-help therapy class, he began to say “I am afraid” over and over. Soon he, said, “I began to shake with such force that I lowered myself to the rug, so as not to fall. I was also sweating to the point that I soaked my clothes.” The shaking and sweating lasted upwards of 20 minutes, he recalled. When it was over the fear was gone and he spoke at the demonstration without preparation.

It’s that physical response that people and researchers need to embrace before they can understand emotions, said Scheff, who noted that modern society — especially men — largely has disconnected itself from emotions. “Women understand it a little better because they’ve had good cries and know that they feel better after they’ve cried,” he explained. “Men don’t have much of that, and it’s a hardship in studying emotions.

“There are a lot of people studying emotions now but we’re all going our separate ways; we haven’t found a common denominator,” he continued. “So what I’m telling my fellow emotions researchers is that if you want to be a sailor you have to have sailed across the sea at least once. I sailed across the sea once, so I’m a sailor in this area because I have legitimate grounds for believing something about emotions.”