Marine Species on the Move

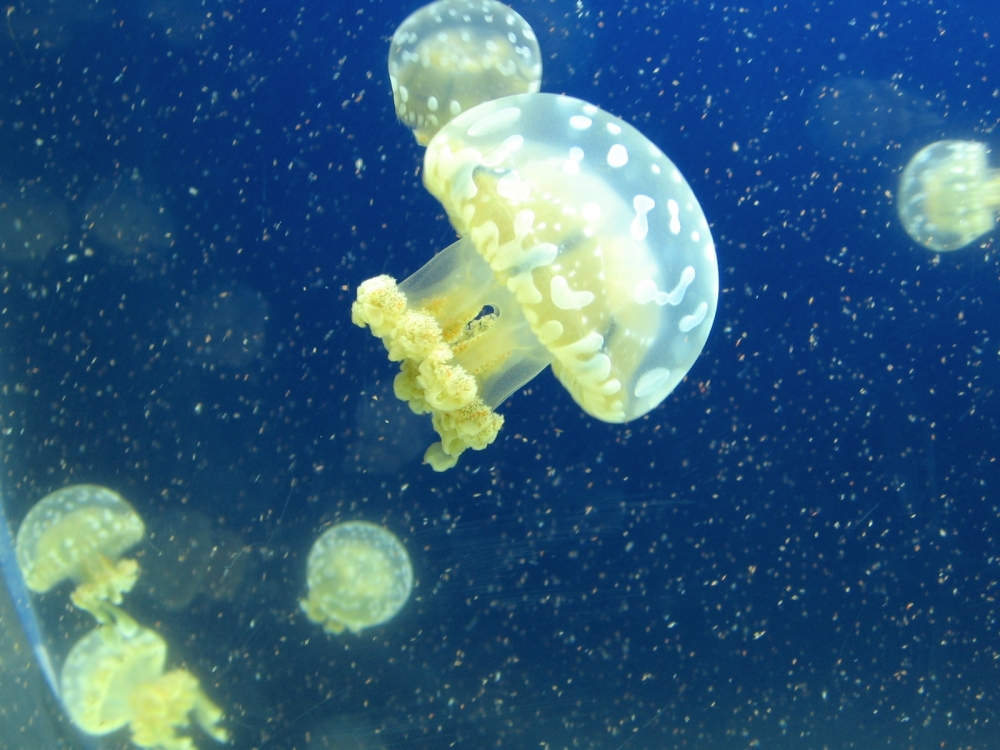

As the world’s oceans warm in response to climate change, marine species are relocating — generally toward the poles — in pursuit of water temperatures that suit them.

A new paper by a group of 10 scientists affiliated with UC Santa Barbara’s National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis (NCEAS) suggests that by the end of this century, warming of the oceans will result in significant global redistribution of marine life. This in turn will increase biodiversity in many areas or lead to extinctions in others, all while creating new kinds of communities less distinct from one another. The research results appear in the journal Nature Climate Change.

“Climate change is going to reshuffle marine biodiversity, creating novel communities,” said Ben Halpern, a professor at the Bren School of Environmental Science & Management and an NCEAS associate. “Our results predict what these changes will look like, but there is a lot we still don’t know about what the changes will mean for biodiversity and for people who depend on that biodiversity — for instance, in terms of seafood and economies linked to ocean tourism.”

In conducting the study, the researchers projected ocean temperatures and then modeled how nearly 13,000 species — more than 12 times the number of species previously assessed — followed changing temperatures into future locations. Similar studies have been based on such complex variables as larval dispersal, population-growth models and other factors for which data is scarce, thus limiting the number of species that could be tracked. “We focus on the simple assumption that species track water temperature, and we have data on temperature preferences for most species,” Halpern said.

As warming continues to cause migration, new species will enter a community before others disappear from it, and species that can tolerate a wider range of water temperatures may not move right away. The results show an unexpected outcome — that migrating species will increase biodiversity in most parts of the ocean — but also that migration will drive a homogenizing process as once-unique communities come to resemble one another. Meanwhile, species that have more restricted ranges — especially those in the so-called Coral Triangle, the center of global marine biodiversity — are more likely to face extinction.

This study emphasizes the need for proactive and collaborative conservation efforts and marine spatial planning around the world in order to combat the impacts of climate change on marine biodiversity.

While the amount that global temperatures will increase due to climate change is still unknown, the researchers suggest that widespread redistribution of existing marine biodiversity will accompany any increase in global temperatures, whether warming is closer to the maximum predicted amount or more moderate.

“We have a chance to minimize the impacts of climate change on marine biodiversity,” Halpern said. “Our simulations show that if we can slow down climate change, changes in biodiversity will be much less than if we leave climate change unchecked.”

According to the authors, one striking finding of this and earlier research on climate-driven migration of marine life is that, previously, shifts in global marine biodiversity took place over geologic timescales and were driven mainly by tectonic events. Current patterns of biodiversity, for example, were established more than 2.5 million years ago. The projections from this study, however, suggest that anthropogenic climate change will cause such biodiversity shifts over the course of a single century.