‘For Freedom and Human Dignity’

There is always hope. For light amid shadows, for compassion in fear, for love from hatred, there is always hope.

It was hope that took them south in June 1965. They were idealistic college kids, many still teenagers, clutching hard to an outsized hope and a belief that they could change the world. Their optimism was shared, and bolstered, by the man who inspired their journey 50 summers ago: Martin Luther King Jr.

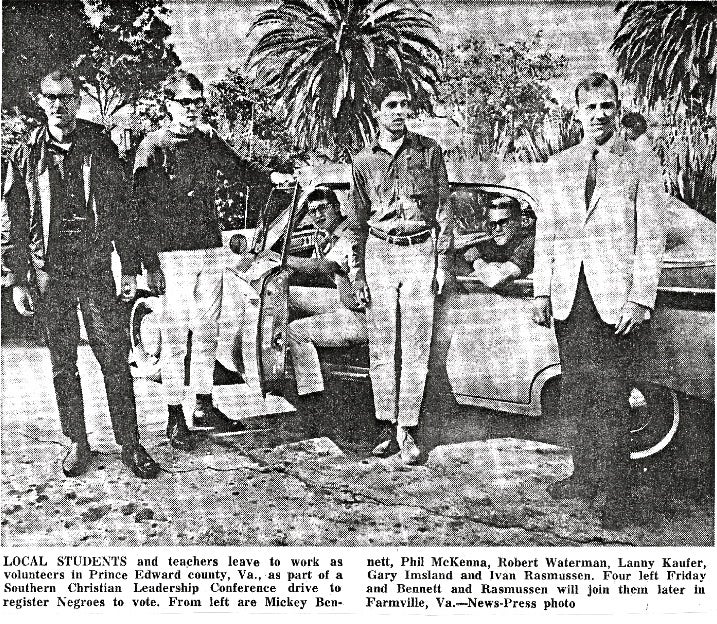

With a characteristically rousing oratory, King welcomed them, some 350 students from universities across the country who had enlisted in the Summer Community Organization and Political Education (SCOPE) project. It was a new effort of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to register and energize black voters as the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965 wended its way through the legislative process.

Coming on the heels of the historic march in Selma, Alabama, SCOPE was a follow-up to, and extension of, the well-known Freedom Summer a year earlier. The hope for the new initiative was not only to register voters but also to seed and grow lasting social change by galvanizing poor black communities.

“How happy I am to see you here in Atlanta, in such enthusiastic and spirit-filled numbers, to become a part of what I believe will be one of the most significant developments ever to take place in our whole struggle for freedom and human dignity,” King said to kick off a weeklong orientation and training in nonviolent action. “You are here because history is being made here, and this generation of students is found where history is being made.”

Among the crowd of students that day was a contingent from UC Santa Barbara. The seaside campus was a stop on a SCOPE recruiting tour headlined by noted activist, SCLC leader and trusted King confidant Hosea Williams.

“When I heard him speak, I was ready,” recalled Lanny Kaufer, who was a freshman at UCSB in 1965, when Williams spoke on campus. “That feeling that things I’d taken for granted, I suddenly realized, were not the way I thought they were. The feeling that somebody should do something about this, about civil rights, and I realized I am somebody. I can do something.”

‘For Decency and Brotherhood’

Sussex County, Virginia, was a far cry from Santa Barbara. Rural, extremely poor and completely segregated, it was a world away in geography and ideology alike.

The UCSB group arrived in Sussex with hopeful hearts and open minds. They were welcomed into the black community where they were to stay with kindness, enthusiasm and no lack of wonder.

“During dinner on our very first night, the young son of the family that hosted me kept staring and staring,” Kaufer, of Ojai, said recently. “His mother noticed and told him it wasn’t polite to stare, and he said, ‘But Mama, he eats just like we do.’ That moment I will never forget — that realization of what racial segregation does to people. To go out on the street the next day with the kids all around us — them wanting to touch my arm and commenting that my skin felt just like theirs — it was a revelation.”

Just hours into their assignment — the SCOPE volunteers were dispatched in clusters to similar counties across the South — Kaufer and his fellow students were already seeing, on a small scale, how King’s bold prediction could come to pass.

“You will do far more this summer than teach literacy, canvass for voters, educate Negroes in community organization,” King had told them in Atlanta. “You are going to make the entire nation a classroom. You’re going to teach tens of millions that ugly facts of injustice exist — and yet they can be overcome by a passionate zeal for decency and brotherhood.”

That zeal is what had first inspired Robert Waterman to join the Santa Barbara SCOPE chapter. Readying to transfer from Santa Barbara City College to UCSB in 1965, he was an Army veteran with a keen interest in civil rights and, he said, an innate pull toward activism.

“Even in the service, I had been reading about it — ‘The Fire Next Time,’ by James Baldwin, and other books — and paying attention to the bus boycotts and all that,” Waterman said recently. “And I had a black commanding officer so we talked a lot about it. So I was attuned to it. And I liked the concept of nonviolence, I liked the recruiters and Hosea Williams and the whole thing. I felt a draw to it for sure. It seemed like the right thing to do.

“The most powerful things to me were the person-to-person connections and the way that changed people and empowered people and woke them up to something deeper inside,” added Waterman, of New Mexico, where he founded and long ran Southwestern College, a graduate school in Santa Fe. “And that was King’s thing: nonviolent action, an inner strength and inner awareness of a spiritual power, and how once you see that, it becomes the guiding light for your outer activity. Nonviolent demonstrations woke people up to some deeper ethic.”

‘One Person at a Time’

It was an ethic that Peggy Poole, then Peggy Ryan, felt was instilled in her from a young age. Raised in a staunchly and actively Democratic household, she was a teenager stuffing envelopes and distributing fliers alongside her father for John F. Kennedy’s campaign. She also had neighbors who were Holocaust survivors, which she credits for an early “heightened sensitivity to people being treated unfairly for things that had nothing to do with their character — just pure prejudice.”

“From a young age I had a very deep belief, which I hold to this day, that everyone deserves to be treated with dignity and equal opportunity,” said Poole, who sought out and joined SCOPE on her own as an 18-year-old freshman at Chico State University. She was assigned to travel and work with the UCSB chapter during the orientation week in Atlanta.

“My parents kept all my letters from that summer and in one of them I say, ‘I’ve never been happier,’” Poole recalled recently. “It was because I had a sense of purpose and solidarity. And there was so much courage. There was dignity. These were poor people living in incredibly difficult circumstances, and a lot of them weren’t educated or politically savvy at all. But they believed in what was right. That made a huge impression on me.

“People really put their lives on the line for basic things — for their right to vote — and it’s not exaggerating to say that,” she added. “It was a very happy time for me. I was doing something meaningful, with people who were very inspirational. We were seeing people at their finest. What I learned is that you treat everyone with dignity and you can make a difference, one person at a time.”

The SCOPE team made a difference in Sussex County.

Working shoulder to shoulder with residents, they helped the community organize peaceful demonstrations in their neighborhoods and town centers. Singing freedom songs and carrying protest signs, they marched outside the county courthouse, which was then open only three hours per week for voter registration. There was also a $3-per-person fee to register — “a barrier that was put in place to keep people away,” said SCOPE veteran Phil McKenna, who still lives in Santa Barbara. “They were disenfranchised.”

As an extension of King’s belief that, as he told the students at orientation, “one of the most significant steps that the Negro can take at this hour is that short walk to the voting booth,” expanding the hours of registration in Sussex became a core focus of the UCSB group’s activities that summer. By the time the Voting Rights Act was enacted in August 1965, they had succeeded in that effort.

And it wasn’t just Saturday hours that they won. The group’s victory with the registrar also served as a bolt of energy for the black community in Sussex — the youth in particular — where only months later they would force the integration of local schools.

“They were really fired up after that summer,” Kaufer said. “About the schools especially — the kids really took that up. They wanted it and they got it.”

With the guidance of King and SCLC field staff, the SCOPE volunteers also helped the community set up a local “improvement association” meant to carry on indefinitely the efforts and advocacy sparked that summer. The Sussex Improvement Association still operates today, focusing primarily on issues of poverty.

“That was the real brilliance in King’s strategy,” Kaufer said. “He made sure we wouldn’t be just some flash in the pan and then disappear. This was about empowering them.”

The empowerment would go both ways.

‘There is Always Hope’

After SCOPE, Kaufer eventually left UCSB and, for a time, college life altogether, before finishing his biology degree at UC Santa Cruz. He then went on to become a high school teacher and musician — and a prolific social activist. The environmental movement became, and remains, a passion.

The same goes for McKenna, who earned a degree in sociology and had a long career in finance before retiring into some full-time activism of his own. He is currently the president of the Gaviota Coast Conservancy.

Waterman returned to the South a second summer, working this time in Georgia and participating in James Meredith’s March Against Fear, in Mississippi. He credits his experiences for the spiritual awakening that inspired his education in counseling and therapy and ultimately led him to found his successful college in Santa Fe.

Poole became active in the antiwar movement during Vietnam and served a tour with VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America), a domestic version of Peace Corps. For many years she has volunteered her time with the homeless and underserved communities in California’s Bay Area, where she lives and still works as a nurse practitioner.

“There was a feeling at the time that you could change the world,” McKenna said of their shared optimism then. “Maybe it was a naive feeling but it was very empowering, and I certainly embraced that feeling that I could make a difference. We were open to it. We were looking for it. We were searchers. It was smaller, it was simpler and the issues were right in front of us. You could organize, you could make a difference and there were people there to help you. That was a wonderful environment to be in.

“I think we can always do better,” McKenna added. “I think there’s always hope. I think there’s always the potential for change. On the other side, you can only do what you can do. But if you don’t do it, you’ll never know what difference you could have made.”

Kaufer, McKenna, Waterman, Poole and fellow UCSB SCOPE alumni Ivan Rasmussen and Gary Imsland will gather on campus this week for a 50-year reunion featuring a presentation by Kaufer and a Q&A session with the whole group. Co-sponsored by the UCSB Department of Sociology and the Black Student Union, the event will be held in Mosher Alumni House, on Thursday, April 16, at 7:30 p.m. It is free and open to the public.