'We Inherit the Trauma and It Shapes Us'

Irina Vladi Wender didn’t live through the Holocaust. Neither did her mother. But they bear scars. Each, in her own way, has coexisted with a legacy of the Holocaust handed down by Wender’s grandmother, a Soviet Jew in occupied Belarus.

“I grew up on the stories,” said the lecturer in UC Santa Barbara’s Department of English. “I’m from what used to be the Soviet Union, so my family was directly impacted by the war. They weren’t in camps, but the place where we lived was immediately occupied the moment the war started. It was right across the border from Poland.”

When Wender began her doctoral studies, she had no intention of becoming a Holocaust scholar. But no matter what direction she took her research, somehow it always brought her back to the concentrations camps and the original event.

“My perspective is driven by my own biography,” she explained. “I think there’s a separate event that second and third generations witness. We inherit the trauma and it shapes us. We’re being raised by people who have gone through it. Obviously, there’s a different impact, and there is a degree of separation, but we grew up on this spectral event that we can’t place anywhere. We don’t have a space for it.”

Finding that space is the challenge of generations who didn’t experience the horrors of the Holocaust, or even have a close connection to it, but are required for humanity’s sake to remember it. “I think that museums are often well-meaning mistakes,” she said. “And I know that sounds off. They’re trying to accomplish something, and I think that’s admirable — to remember is the right thing. The trouble is, it still happens. Not in exactly the same way, not to the same people, but it happens again and again. I’ve always found it troubling.”

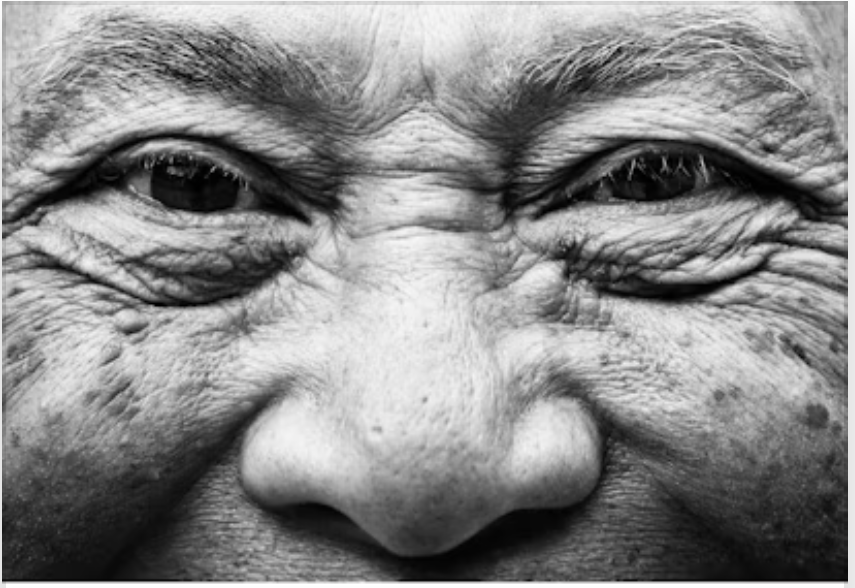

Wender is disturbed by images of people in concentration camps, not so much because of what they represent, but because of what they don’t show. “The images of these people in this terrible state desubjectifies them and makes objects out of them,” she said. “There you are staring at images of people who had jobs and families and normal lives before the war, and you’re seeing them at their worst. And that’s how they’re remembered. They’re no longer people; they’re objects we look at to remember something for our own purposes. In an effort to do something good, and in an effort to remember, we create an entirely different atrocity, I think.”

Nor do the concentration camps themselves — Auschwitz, Birkenau, Dachau, Bergen-Belsen, Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald, Terezín, Mauthausen — really help us feel the enormity of what happened during the Holocaust. “I think rebuilding these factories of death is horrific,” she said. “The land, the boundaries, the topography itself would retain the same horror. Leaving them to rot slowly would be better. It would make more sense to me.

“We need to remember not so much the specific places — Auschwitz and the others, obviously we have to remember what happened there, remember the people who died there, we must — but we can’t go there and truly experience it,” Wender continued. “Though someone once told me she had. And my response was, ‘Really? Were you starving? Did you have gangrene anywhere? Did you have typhus? Were you naked? Was it freezing?’”

To Wender, monuments such as the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin provide a more visceral experience. “It’s intense because once you’re in there it imposes on you physically,” she said. “Everything about it is so well thought out. There are no boundaries — you can wander in and you can wander out. But even if you see the exit, you still have to go through all of it to get out. Once you get into the thick of it with the high, overwhelming blocks of concrete, no matter how claustrophobic you might be getting, you still have to pass through it to get out. And I think that’s what we have to acknowledge.”

Wender described a similar monument in a small village near Belarus. During the Nazi occupation, the villagers were crowded into a barn, and the barn was set on fire and burned to the ground. “They erected a memorial there, but you don’t see the burnt barn — or the barn rebuilt,” she said. “You see a memorial of the absence. You see an interpretation of the absence. And that’s the key to these places. They acknowledge what’s not here anymore.”

So what’s the key to honorably, authentically and ethically remembering an experience that is not our own? “Somewhere we have to find a space for our own trauma,” she explained. “We have to define our own original event. Because it’s not the camp and it’s not the occupation. We weren’t there. We need to define something different, something that allows those of us who grew up with it — not in it, but with it — to acknowledge that hurt. Because that’s what the world is going through.”

Coming Wednesday: History professor Harold Marcuse looks at how remembrance changes over time.