Ukrainian Occupation

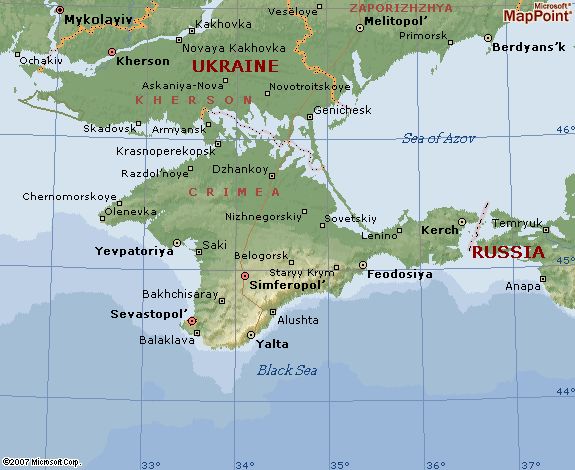

As Russian troops continue to occupy Crimea — the southernmost area of Ukraine — all eyes are on Russian President Vladimir Putin as he plans his next move and on the United States and Western Europe as they organize their response.

What might be behind Putin’s seemingly sudden decision to move into Crimea, and what might he hope to accomplish? And how might sanctions be used both as a punitive measure and a means of preventing further Russian expansion into Ukraine?

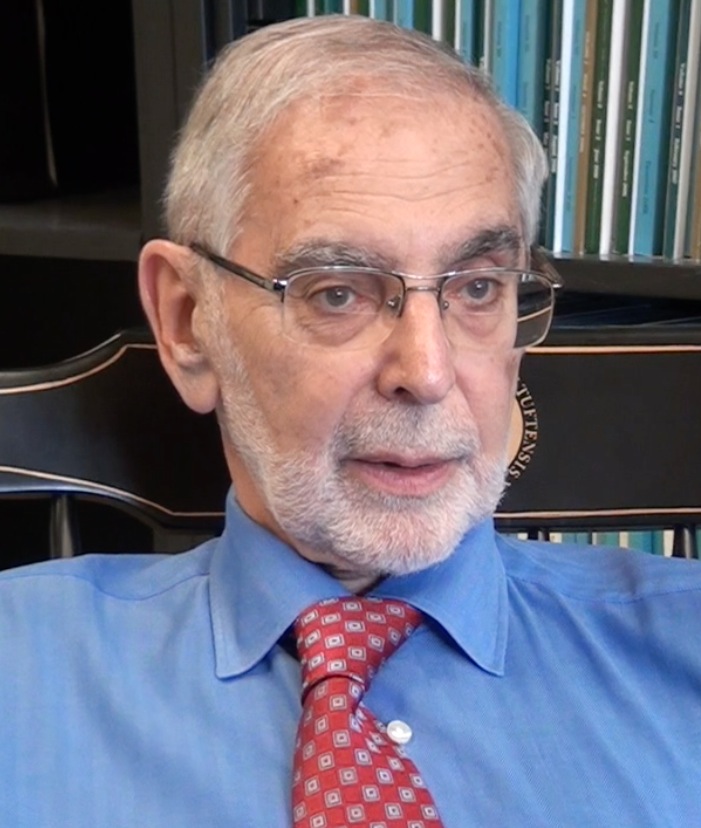

“The European Union has for several years been negotiating an association agreement with Ukraine, and the time had come for the grand signing,” said Benjamin J. Cohen, the Louis G. Lancaster Professor of International Political Economy at UC Santa Barbara. “A meeting was scheduled for the signing, and that was the moment at which the Russian government felt it had to move or it would irrevocably lose a degree of influence over Ukraine.”

According to Cohen, the Russian government under Putin has been trying to create its own equivalent to the European Union. Called the Eurasian Union, it includes countries such as Belarus and Kazakhstan. But key to the project’s success is participation by Ukraine. “So that was what accounted for the particular timing,” he said. “For Russia, it was then or never.”

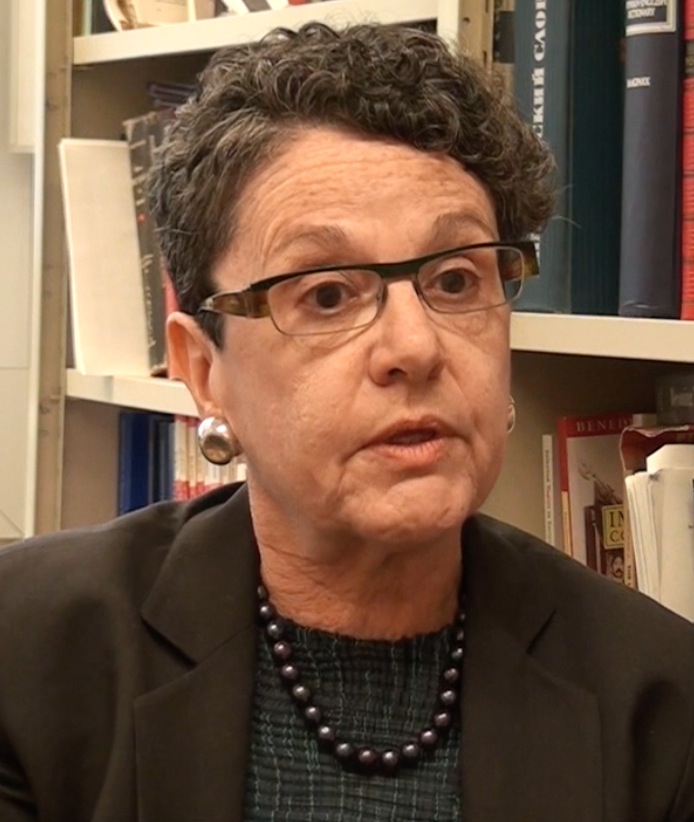

Cynthia S. Kaplan, a professor of political science at UCSB and a specialist in Russian, Tatar, Baltic and Kazakh politics, cites opportunity as part of the impetus behind Russia’s current action. “There was opportunity because of instability in Kiev,” she said.

Whatever the timing, Kaplan suggested that the action itself has multiple goals. “And they’re probably graduated,” she said. “I think the minimal goal is to have a secure lock on the submarine base in Sevastopol. Maintaining influence on the political process of Ukraine, outside the Crimean peninsula is also a high goal — although, as we learned during Putin’s press conference [on Monday], control of Crimea might be a separate goal from maintaining influence in Ukraine as a whole.”

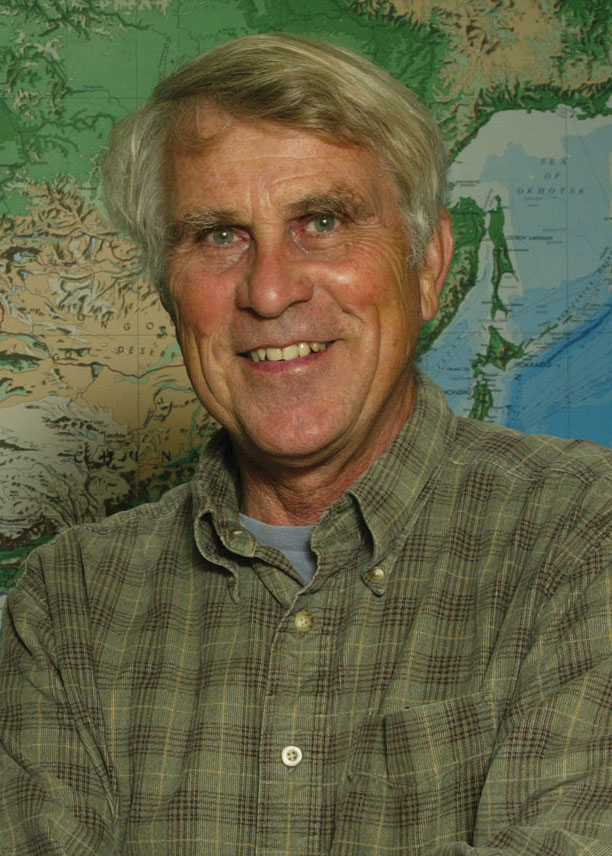

Noted Mark Juergensmeyer, professor of sociology at UCSB and director of the campus’s Orfalea Center for Global & International Studies, “Clearly he wants to protect the Russian military bases in the Crimea, but it’s also a way of reasserting Russian control over a section of Ukraine that was until 1954 part of Russia and has a long Russian connection.”

The scholars agree that while the U.S. and the Western European countries don’t have much in the way of military influence over Russia’s advancement in Ukraine, economic sanctions can have a significant impact. “The U.S and Western Europe together don’t have much leverage because Russia can get from other sources the few things it needs to import from the outside,” said Cohen. “Its primary exports are energy — natural gas and oil — and the rest of Europe is very dependent on those shipments. In fact, that’s one reason why Ukraine is so important. The natural gas goes through a pipeline that crosses Ukrainian territory.”

“So we don’t have much leverage in terms of trade, but we do have leverage in terms of finance,” he continued. The Russians need access to dollars, and they need to be able to use their dollars for international commerce, Cohen explained. Eighty percent of their revenue comes from oil and natural gas, and those commodities are sold in markets denominated in dollars. “They need to have functional bank accounts in dollars,” he said. “And the U.S. has already shown in the case of Iran that it’s possible to use that dependence on dollars as a form of leverage.”

Sanctions wouldn’t completely eliminate Russian access to dollars — the global financial network is huge and complex, according to Cohen, and people who are determined to evade sanctions or controls can do so through offshore financial centers and the like. However, sanctions would severely limit that access. “And that would be a cost to the Russian government,” he said. “That was the word used by President Obama. He said there would be costs. And that would be the most potent cost we could impose.”

Juergensmeyer noted that even without sanctions officially in place, the Russian economy is suffering. “Already today the Russian stock market has dropped, the value of the ruble has fallen and interest rates have risen, making money tighter.”

Kaplan added that the U.S. and Western Europe also can have a lot of symbolic influence. “That’s why the Secretary of State toured Independence Square in Kiev. It was important for him to be seen at such a historic spot.”

Influence aside, Kaplan argued that the U.S. and Europe make their intentions and preferences clear. “Putin may have his own logic and calculations of risk assessment, but we have to be clear about what our expectations are.”

Of the notion that the current situation is reminiscent of the Cold War, Kaplan disagrees. “Crimea is not Berlin with tanks sitting on both sides of the border,” she said. “Nor do I think this is the Cuban Missile Crisis. Do I think it’s a turning point in Central Europe in terms of Russian influence? Yes. It’s a serious issue. But it’s probably not one of strategic security for the United States.”

How the situation will play out is anyone’s guess. Cohen suggested the best-case scenario would be for Russia to agree to replace its military presence with troops from neutral countries or troops sponsored by the United Nations. But Kaplan is not optimistic about such a resolution. “Sending neutral troops would be a face-saving gesture, but it probably will not be used,” she said. “There’s no reason for Putin to use it. His goal at the very minimum is to have a secure military situation in Crimea.”

The most likely scenario, according to all three scholars, is a stalemate of sorts. “My guess is that Crimea will effectively secede de facto — if not formally — and go back to Russian jurisdiction, where it was before 1954, when Khrushchev decided to hand Crimea over to Ukraine,” noted Cohen. “The majority of Crimean people are Russian citizens or ethnic Russian.”

Still, while many Crimean people might support Putin’s objectives in Ukraine, Kaplan points to international law and sovereignty to underscore the illegality of Russia’s recent action. “The Budapest Memorandum was based on the Helsinki Accords of 1975,” she explained. “Borders were set in Europe to finalize and recognize them after World War II. Those cannot be violated. Period.”

One aspect of the Ukrainian situation not fully explored, however, involves the Crimean Tatars, who have occupied that area since the Ottoman Empire and ruled Crimea until about three centuries ago, Cohen said.

“This is a group of people who were exiled by Stalin to Siberia and to Central Asia, and who only during perestroika — during the Gorbachev years — were able to make their way back without any state support,” said Kaplan. “Crimean Tatars support the government in Kiev, and if Russia allows Russian nationalists within Crimea to have their own policy preferences, Crimean Tatars, even more than Ukrainians, will be the losers in this.”