The knowledge box on the hill. So goes Harvey Schechter's favored idiom for his alma mater, an apt description adopted from a co-worker during his bellhop days at the former Carrillo Hotel in downtown Santa Barbara.

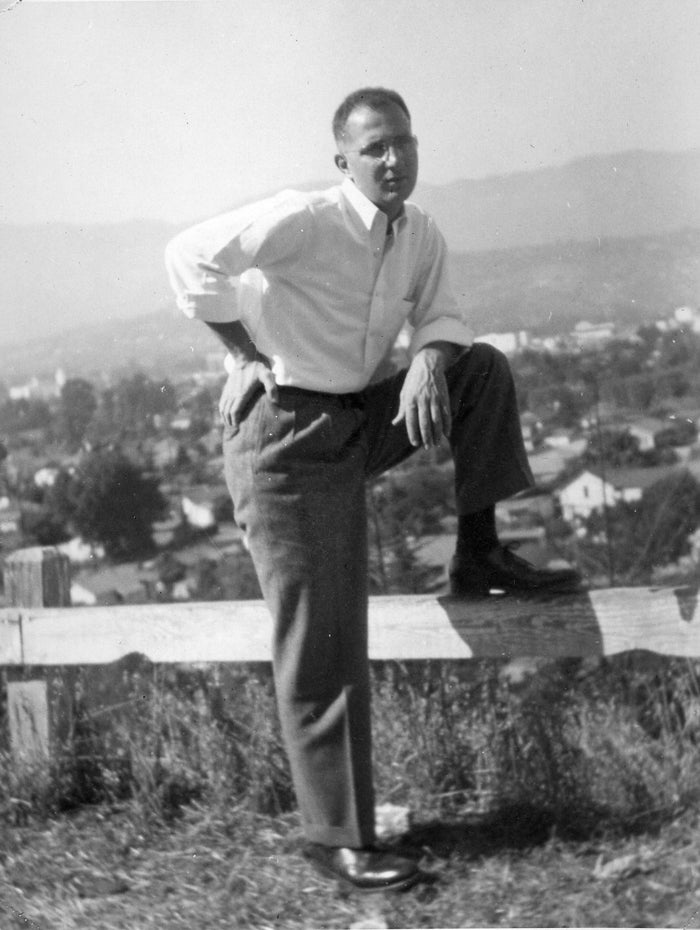

It was the early 1940's, and what would soon become UC Santa Barbara was still a 14-acre Riviera campus called Santa Barbara State College. First enrolling in 1942, Schechter earned a bachelor's degree in sociology in 1947 –– one of 122 graduates that spring –– just three years after the school was incorporated into the University of California system.

Fast forward 56 years and Schechter, 89, remains actively involved. He is a lifetime member of the Alumni Association (and former member of its board of directors), and, since 1996, a trustee of the UC Santa Barbara Foundation. As a pledge of their mutual belief in and devotion to the university, Schechter and his wife of 57 years, Hope, included the campus in their estate plans: 80 percent of their money will be left to UCSB, earmarked for underprivileged students.

Schechter is also among the UCSB's most devoted and outspoken champions, singing its praises and advocating for its advancement to fellow alumni, to students both present and prospective –– even to complete strangers. He can't help but effuse at every opportunity about the university he (half) jokingly refers to as Hope's "love rival."

"What is it about Santa Barbara?" Schechter asked rhetorically. "It's ethereal. It puts a spring in your step. I can't document it, but I know that with pride I say, ‘UC Santa Barbara.'

"What Chancellor Yang has done here is remarkable. I've told people I don't think I could get in today, and I was an A student. These kids today are so smart. And the things they're doing in science and literature and art and music, my god. I'm overwhelmed by what UCSB has become."

Schechter arrived in Santa Barbara in 1941, a sickly kid from Brooklyn sent to recuperate from rheumatic fever in the West's clean air and warm weather. He lived at La Loma Feliz, a private ranch school run by a local doctor his parents found through the New York Heart Association. He finished high school and tended the horses. When he started college, he rode one of those horses, a mare named Chica, to campus. It was a surreal existence for a big city boy whose only previous exposure to horses were those he saw in movies.

"I thought about my brother, who went to college in New York City by subway –– a hole in the ground –– while I was on a horse riding beautiful Mission Canyon," Schechter recalled with a laugh. "My bad heart gave me a real leg up."

"I've said to people that being on the campus at that time was like being in heaven and still being alive. It was wonderful," Schechter said. "In the 1930's, Hollywood made movies about college life. I was living it in the 1940's –– beach parties, small classes. Some of the buildings here are named after my professors. Girvetz, Ellison, Buchanan –– these were my professors. We had 20, 25 to a class. It was magnificent."

Fond memories of his college days flow free and easy from Schechter, whose effusive enthusiasm for Santa Barbara has deep roots. As an active student passionate about his campus, Schechter was "one of the reactionaries" who pitched a collective and vocal fit when school color and mascot changes were proposed. To better align with the UC system, he said, it was suggested that Santa Barbara's green and white be swapped out for blue and gold, its Gaucho replaced with a Cub.

"There were arguments to the student council, letters to the editor of the student paper –– big fight," Schechter said. "Finally someone came up with a compromise: ‘If you'll take blue and gold, they will accept Gauchos.' We said, ‘You got a deal.'"

He was getting a good deal himself. In those days, a public college education was truly available to anyone who wanted it. Tuition essentially didn't exist; students needed only to pay a registration fee that Schechter said amounted to $17 per semester.

"When I said to one of the trustees, ‘My school at Santa Barbara was free,' she said, ‘It wasn't free, Harvey. Somebody paid for it.' That really registered with me," he said. "So Hope and I wrote our wills so that the bulk of our money goes to the UC Santa Barbara Foundation to help needy students.

"How could I not make available to some kid I don't know what was done for me by people who didn't know me? Everything was free –– free in the sense that those who participated didn't have to pay. The $17 registration fee covered athletic events, health coverage, everything –– $17."

Giving back to the campus that gave him so much was a no-brainer, Schechter said. Though he went on to earn a master's degree from UCLA and a decades-long career with the Anti-Defamation League, retiring in 1993 as its Western States director emeritus, it is his time at UCSB that he refers to as "the happiest, most wonderful" of his life, a "wonderful, fantastic, unreal existence."

On the invitation of Chancellor Yang, Schechter spoke to a group of UCSB applicants at an event in Los Angeles last spring. Agreeing to impart two minutes of wisdom, he told the Gaucho hopefuls: "If you go to Santa Barbara, you will benefit. Here I am getting very old, and I'm still benefitting from what Santa Barbara gave me. There is a cache that Santa Barbara has that nobody else has. Decades from now, if you come here, you will say, ‘Remember that bald guy who told us we should come here? Boy was he right.'"

Related Links