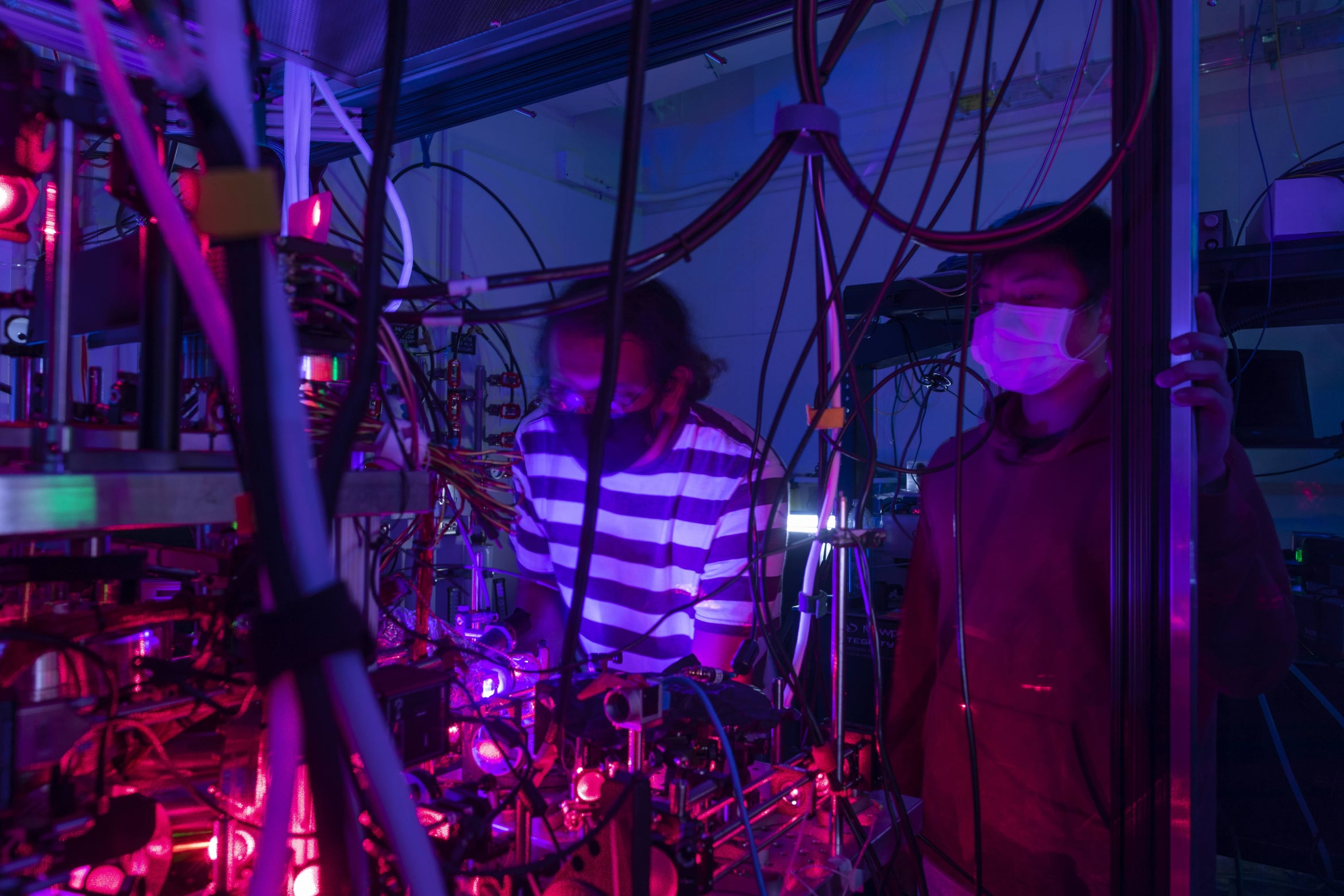

UCSB Scientists Develop New Nanoscale Imaging That May Lead to New Treatments for Multiple Sclerosis

Laboratory studies by chemical engineers at UC Santa Barbara may lead to new experimental methods for early detection and diagnosis –– and to possible treatments –– for pathological tissues that are precursors to multiple sclerosis and similar diseases.

Achieving a new method of nanoscopic imaging, the scientific team studied the myelin sheath, the membrane surrounding nerves that is compromised in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS). The study is published in this week's online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

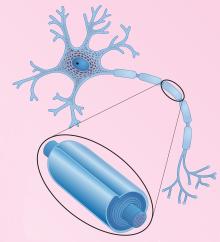

"Myelin membranes are a class of biological membranes that are only two molecules thick, less than one millionth of a millimeter," said Jacob Israelachvili, one of the senior authors and professor of chemical engineering and of materials at UCSB. "The membranes wrap around the nerve axons to form the myelin sheath."

He explained that the way different parts of the central nervous system, including the brain, communicate with each other throughout the body is via the transmission of electric impulses, or signals, along the fibrous myelin sheaths. The sheaths act like electric cables or transmission lines.

"Defects in the molecular or structural organization of myelin membranes lead to reduced transmission efficiency," said Israelachvili. "This results in various sensory and motor disorders or disabilities, and neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis."

At the microscopic level and the macroscopic level, which is visible to the eye, MS is characterized by the appearance of lesions or vacuoles in the myelin, and eventually results in the complete disintegration of the myelin sheath. This progressive disintegration is called demyelination.

The researchers focused on what happens at the molecular level, commonly referred to as the nanoscopic level. This requires highly sensitive visualization and characterization techniques.

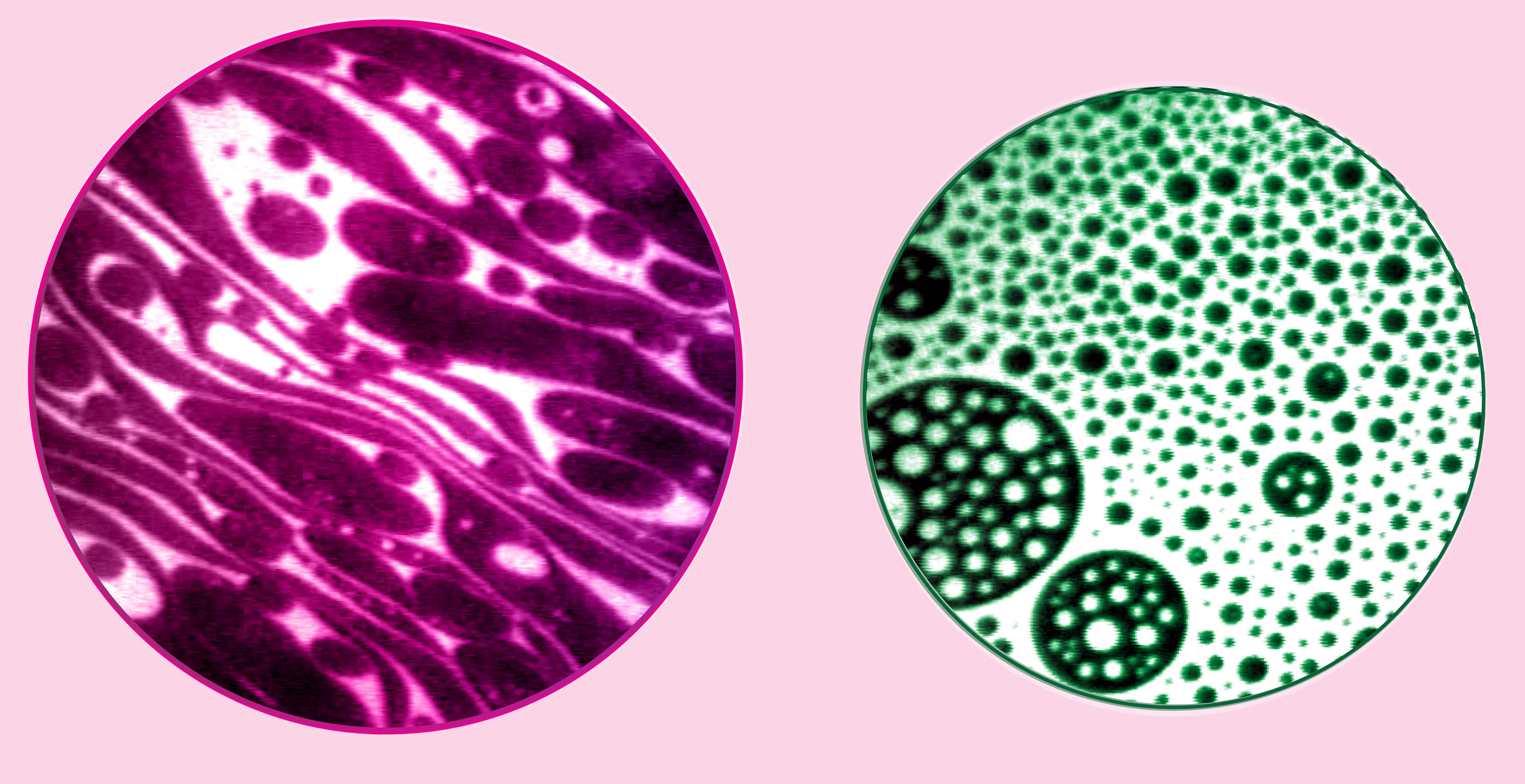

The article describes fluorescence imaging and other measurements of domains, which are small heterogeneous clusters of lipid molecules –– the main constituents of myelin membranes –– that are likely to be responsible for the formation of lesions. They did this using model molecular layers in compositions that mimic both healthy and diseased myelin membranes.

They observed differences in the appearance, size, and sensitivity to pressure, of domains in the healthy and diseased monolayers. Next, they developed a theoretical model, in terms of certain molecular properties, that appears to account quantitatively for their observations.

"The discovery and characterization of micron-sized domains that are different in healthy and diseased lipid assemblies have important implications for the way these membranes interact with each other," said Israelachvili. "And this leads to new understanding of demyelination at the molecular level."

The findings pave the way for new experimental methods for early detection, diagnosis, staging, and possible treatment of pathological tissues that are precursors to MS and other membrane-associated diseases, according to the authors.

All of the work reported in the paper was completed at UCSB, although some of the authors have moved to other institutions. In addition to Israelachvili, the other authors are Dong Woog Lee, graduate student in UCSB's Department of Chemical Engineering; Younjin Min, now a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Chemical Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Engineering; Prajnaparamitra Dhar, now assistant professor in the Department of Chemical Engineering at the University of Kansas; Arun Ramachandran, now assistant professor in the Department of Chemical Engineering and Applied Chemistry at the University of Toronto; and Joseph A. Zasadzinski, now professor in the Department of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science at the University of Minnesota.

† Top photo: These are fluorescence images of lipid domains in model (laboratory reconstituted) myelin monolayers showing coexistence of liquid-ordered (dark) and liquid-disordered (pseudo-colored) phases. Depending on the conditions (e.g. liquid-disordered (pseudo-colored) phases. Depending on the conditions (e.g. lipid composition, surface pressure, temperature), the lipid domains can exist in various shapes including striped (left) and circular (right).

Credit: Images courtesy of Younjin Min, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

†† Middle photo: Shown is an illustration of a neuron, which is the basic functional unit of the nervous system. Enlarged portion indicates myelin sheath which is a multilamellar membrane surrounding the axon of neurons.

Credit: Dottie McLaren

Related Links