In a little less than a year, from July 2008 to May 2009, the Santa Barbara area was hit by three terrifying wildfires. All took a physical and mental toll on the citizens of Santa Barbara, Goleta, and Montecito. A number of factors –– mandatory evacuations, homes in flames, concern for loved ones –– created stress for those who live in the Santa Barbara area.

The impact of the fires on the mental health of local residents is the focus of an interdisciplinary project involving two UC Santa Barbara researchers and the UCSB Social Science Survey Center, which conducted a telephone survey of residents in the fire zone. The researchers –– Walid Afifi, a professor in the Department of Communication, and Erika Felix, a researcher in the Gevirtz Graduate School of Education –– note that they are still analyzing the results of the survey and will release their final report in the near future. But their preliminary analysis of the findings has enabled the pair to begin to paint a picture of the ways in which the fires and the danger they represented affected area residents.

The survey covered the following wildfires:

Gap Fire, July 2008, 9,443 acres burned, four structures destroyed, 12 people injured.

Tea Fire, November 2008, more than 2,000 acres burned, more than 200 homes destroyed, 13 people injured.

Jesusita Fire, May 2009, 8,733 acres burned, more than 90 structures destroyed or damaged, 30 people injured.

Thousands of people were evacuated during the fires. The communities most affected by the fires were the target control group for the pollsters who conducted the random-digit phone survey. The sample size was 402, with 74.8 percent from Santa Barbara, 20.6 percent from Goleta, and 4.5 percent from Montecito. Fifty-eight percent of the respondents were female. Interviews were conducted in English and Spanish, as appropriate.

"We narrowed the survey to the ZIP codes of the communities that were affected by the fires," said Felix. "Obviously, a large proportion of our population has been affected by these evacuations. In the Jesusita Fire, the media reported about 30,000 people evacuated."

Among those who responded to the poll questions, 39 percent were evacuated during the fires. Thirteen percent were evacuated two or more times during the fires –– some of them evacuated twice during the same fire. "That's a pretty dramatic figure," Afifi said. "There are very few places in the world where you see that (multiple evacuations) in a short period of time. So one would imagine that the stress is pretty high in a place like this when you see so many people evacuated.

"We have found that multiple evacuations do have a significant effect on mental health, over just a single evacuation," he added. "In fact, in some ways, the ones who were evacuated just once were somewhat similar to those who were not evacuated at all. It's that second time that seemed to make the most noticeable difference."

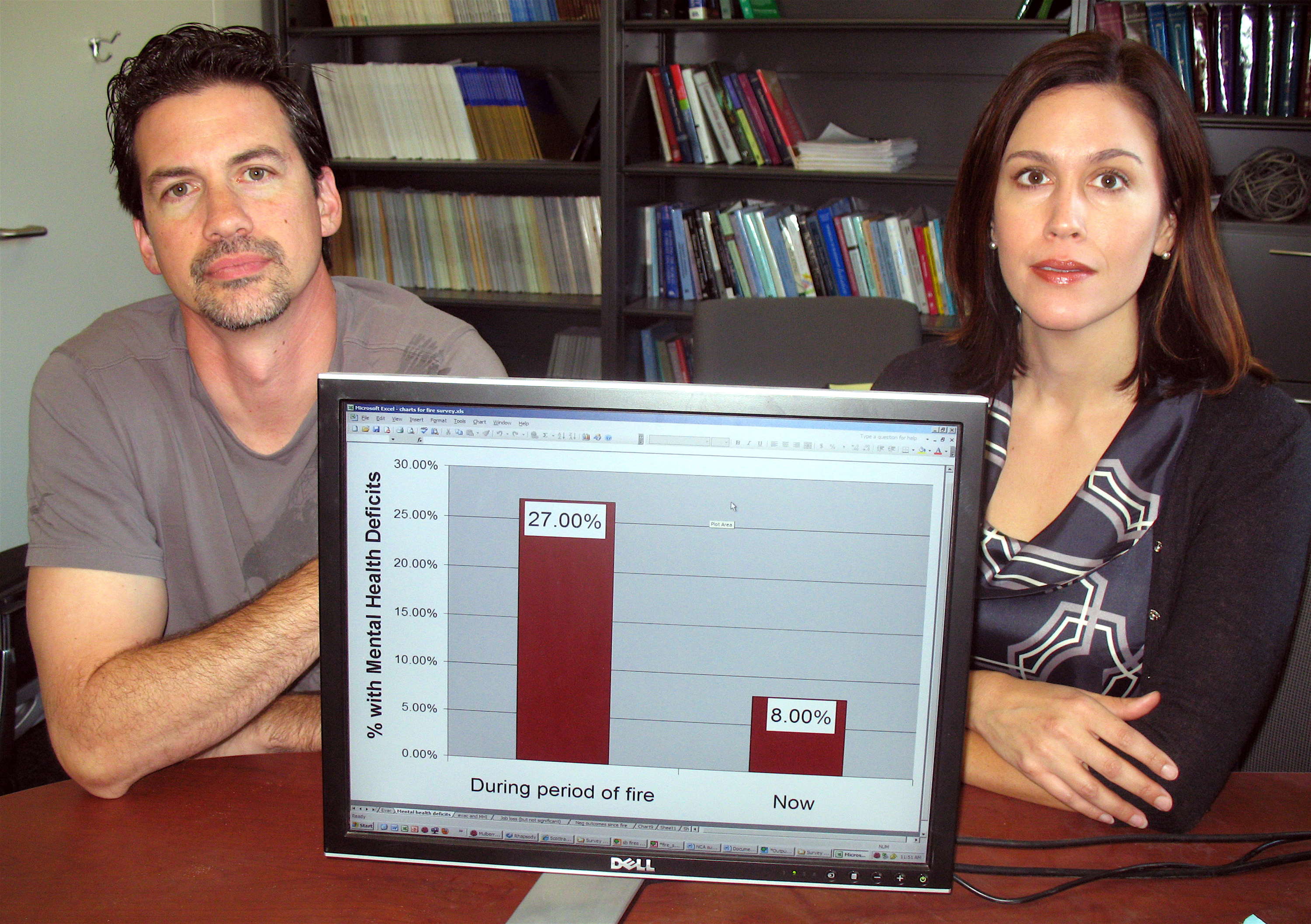

The survey found that more than one in four of the respondents, whether evacuated or not, experienced symptoms of loss of mental health during the fires. "The data are pretty clear: Evacuations affect mental health," Afifi said. "But the data also give hope –– the vast majority of us are quite resilient," he added, pointing to evidence from the study that only 8 percent of the respondents were still reporting symptoms today.

The impact of the fires on various income groups was also studied. "Although the evacuations related to these fires were generally for high-income areas, the people making less than $20,000 were dramatically more likely to be psychologically impacted than the other groups," Afifi said. "In our sample, the low-income groups were less likely to be evacuated, but more likely to be negatively affected. When you find people who were not evacuated had an even worse experience than the people who were, it points to the need to understand these effects more broadly than simply whether people were evacuated or not."

The survey was the first to closely examine people's uncertainties during disasters. Specifically, it focused on uncertainty about personal safety, home safety, and the safety of family and friends during the fires. "We found that all three were strongly related to mental health," said Afifi, whose research focuses on uncertainty. "The more uncertain you were about these things, the worse off you were."

Coping skills also were tested during the fires. "We found that people who cope communally are going to be better off than if they try to cope individually," Afifi said. "We found that was very much true for the low-income groups. Those in the low-income groups who did cope communally had a much greater effect in terms of improving their mental health over time."

The long-term impact on people's lives caused by the stress of the fires was also studied. "There's some hypothesizing that a disaster itself can cause stress, but it also can set in motion a cascading series of life stressors resulting from it," Felix said. "For example, parents might argue more because they're stressed about rebuilding, financial stuff, parenting behavior.

In this study, we were also looking at the role of social support and these life stressors."

What they found was that fire-related stress negatively affected mental health, "but if you have people in your life who can support you, who you can turn to for emotional comfort, or just logistical help –– a place to stay –– then you tended to do a little better," Felix said. While stress was most related to mental health at the time of the fire, even now there is a significant relationship. "It's still impacting it," she said. "And we found that social support had a good, direct effect. It lessens the impact of life stressors."

Finally, the survey studied the use of media resources by those who were affected by the fires. How did those surveyed stay informed? While many cited Web sites and blogs as sources of fire information, the vast majority said that television stations were found to be most useful. "Importantly, though, one thing that we see is that many people are using multiple sources, and that younger populations are increasingly turning to the Web as one of those sources," Afifi said.

Afifi cited one example of coverage that may do more harm than good, given results from this study. "What we saw on television, at times, was a close shot of a house burning that was on for several minutes, then recycled again in future broadcasts. No sense for where exactly this house was burning was ever given. The best they could do is the general area, and even that sometimes wasn't given. People turned to blogs for minute-to-minute information about where the fire was, and where houses were at risk. Media outlets might want to pay attention to the uncertainty findings here, because the quality of their coverage during disasters has a dramatic impact on uncertainty levels in the community. As such, they play a dramatic role in our well-being."

Walid Afifi and Erika Felix are members of a Disaster Research Group that also includes Tamara Afifi, associate professor in communication; Maryam Kia-Keating, assistant professor in education; Gilbert Reyes, professor at Fielding Graduate University; and Cally Sprague, a Ph.D student in education.

This study was sponsored by the Division of Social Sciences, and supported by a Collaborative Research Initiative Grant from the Institute for Social, Behavioral and Economic Research (ISBER), and by a generous donation by Santa Barbara Bank & Trust.

About the UCSB Social Science Survey Center

The Social Science Survey Center provides academic and non-academic clients with resources to conduct CATI telephone surveys, sophisticated Web-based surveys, mail and multi-mode surveys on local, regional, or national populations in several languages. The center has pioneered mixed-data collection modes, coordinating the use of telephone, mail and the Web for maximum effectiveness. Extensive consulting is available on survey instrument design and development, programming, data analysis and interpretation, GIS, and data mining.